Posters are expressive indicators of social conditions. They directly reflect changing attitudes and values of the recipient society. The image change of the industrial development can be properly illustrated by the example of the symbol of the smoking chimney. Especially the political connotations are extremely instructive. The book of patterns, “Allegorien und Embleme” (Allegories and Emblems), published already as early as 1882, contains a coat of arms designed by Franz von Stuck which visualized the industry in the form of a smoking chimney. From this point on, thick trails of smoke, indicating economic success, dominated the pictorial self-portrayal of large companies for a long time. But not only those companies associated with the sooty world of the heavy industry, but even establishments as piano manufactures or representatives from the grocery branch wanted to prove their solidity by means of thick smoke clouds.

During the First World War, which was also a fight about economic perseverance of the individual powers, the image of the factory chimney increasingly gained a political dimension. In most European states, the politicization of the imagery used in the aggressive war propaganda after 1918 was reflected in a polarization of party propaganda. Almost all competing powers seized the at the time evidently so attractive motif of the smoking chimney as a virtually idyllic and unlimited positive symbol of progress, prosperity and optimism toward the future. In the sense of the propaganda’s ‘black-and-white-thinking’, the smoking chimney was on the side of the peace-supporters and as such, the society it dominated had to be defended against enemy powers.

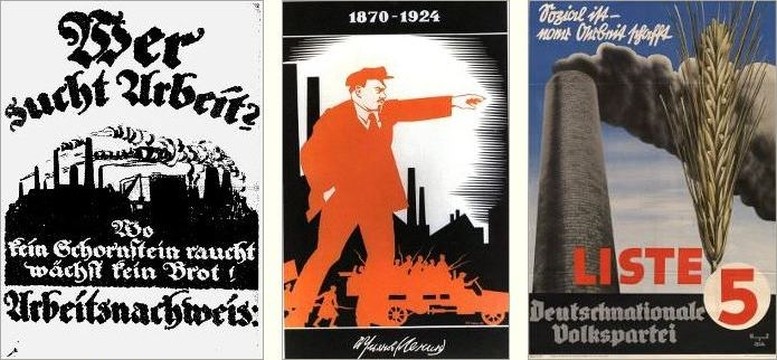

Examples contained the constructivist, reduced posters of the revolutionary Soviet Union and pacifist French posters as well as the publicity works of the entire political spectrum of the Weimar Republic. The case in point was a sheet for the “Werbedienst der deutschen Republik” (Propaganda Agency of the German Republic) by Alexander M. Cay dated 1918. Its catchy slogan read: “When the chimney does not smoke, no bread can be made.” In its ideologically motivated strive to combine art and everyday life, the applied graphic arts reached a remarkable quality peak in early revolutionary Russia. Dimitry S. Moor, one of the most pronounced representatives of this new, active scene, several times portrayed the Marxist fight for the means of production as a controversy surrounding the smoking chimneys in his design. Adolf Strakhov created an icon for the international Marxism-Leninism with his poster at the occasion of Lenin’s death in 1924; it showed the pioneering leader of the revolution in front of a factory skyline. The communists in Germany produced a similar poster there. The lasting effect of the design is proved by the fact that also the national-socialist propaganda of 1937 showed Hitler pose in front of a landscape of smoking industry.

A.M. Cay, 1918 / A.I. Strakhov, 1924 / H.Z. Rüh, 1932

The fact that the symbol of the smoking chimney was generally perceived to be a positive message during times of economic crisis and unemployment can be illustrated by a poster from 1932 of the “Deutschnationale Volkspartei” (German National People’s Party): the photomontage, showing black smoke coming out of a chimney together with an ear of corn, was considered to be a promise for work and bread: “It is socially good – if it produces work.”

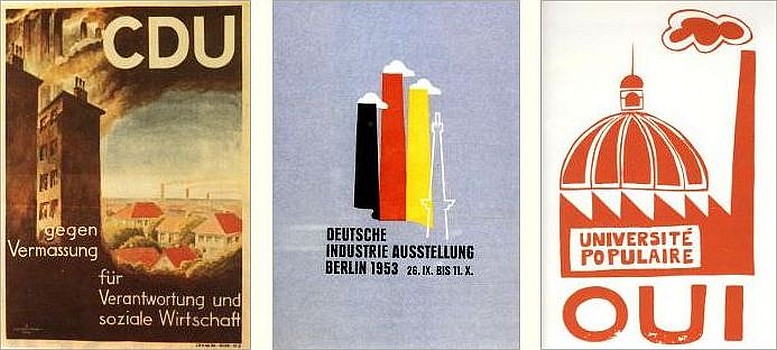

During the years of economic hardship after 1945, the political forces continued to rely on these practically sanctified trails of the smoke of productivity – up until a poster for the German Industrial Fair Berlin, which was published in 1950 and used several times in the following years, showing three chimneys in the German national colours.

Schöning, 1947 / W. Edel, 1953 (first published 1950) / Atelier Populaire, 1968

The first sign of a differentiated use of the motif is documented in an election poster of the CDU from 1947. The slogan read: “Against increasing anonymity. For responsibility and social economy.” By means of a differentiated portrayal of the factory chimneys, the illustration clearly depicted the difference between non-polluting production sites and industrial quarters hostile to humankind. Although the old rightist and leftist symbols of the worker’s world regained a positive meaning with the protest posters of the French student revolts of 1968, the smoking chimney increasingly lost its fascination with the heightened awareness of the problems caused by the methods of production of big industry. The symbol for a desirable social development had become one for ruthless materialism and ecological threat.

With the beginning of the 1970ties, the critical and alternative policies were directed against all those who were “on the side of the chimneys.” Greenpeace demonstrators repeatedly climbed the tall chimneys, the symbol for air pollution, and hoisted banners promoting increased environmental consciousness. While the larger parties paid more and more attention to ecological concerns, clearly distancing themselves from retaining the chimneys as positive signals in their propaganda reservoir, poster activists like Klaus Staeck intentionally played with the image of the air-polluting factory chimney which had turned absolutely negative. One of his most critical productions in this context was a sheet for the First of May celebrations which showed a polluted industrial landscape, supported by the lyrics from the traditional worker’s song: “Brüder zur Sonne, zur Freiheit, Brüder zum Lichte empor” (Brothers towards the sun, to liberty, brothers towards the light).

Bibliography:

Denscher, Bernhard: Rauchende Schlote, zufriedene Menschen. Mythen der Industriekultur,

in: Magie der Industrie. Leben und Arbeiten im Fabrikszeitalter, Wien 1989, S. 34ff.

Revised version of: Denscher, Bernhard: Symbol of the Industry: the Smoking Chimney, in: PlakatJournal 1997/1, S. 7f.

Translation: Jörn Weigelt, PosterConnection.