Henry Steiner’s experience and reputation are international. Born in Vienna and raised in New York, he was educated at Yale – where he studied with Paul Rand – and at the Sorbonne on a Fulbright scholarship. Steiner & Co., founded in Hong Kong in 1964, is one of the world’s leading branding design consultancies. The company’s scope is comprehensive, encompassing corporate identity programs, corporate literature, architectural graphics, product design, packaging, book and magazine design and banknotes. Clients include EF Education First, Hong Kong Jockey Club, HSBC, Standard Chartered Bank and Ssangyong. He has created several series of banknotes for Hong Kong as well as coins for the Singapore Mint.

A distinguished body of work has led to professional recognition: president of Alliance Graphique Internationale; fellow of the American Institute of Graphic Arts, the Chartered Society of Designers and the Hong Kong Designers Association; honorary member of Design Austria and member of the New York Art Directors Club. He has been named Hong Kong Designer of the Year, a World Master by Japan’s Idea magazine, and is included in Icograda’s Masters of the 20th Century. Next magazine cited Steiner as among the 100 people most influential in Hong Kong’s history. He was awarded the Golden Decoration of Honor of the Republic of Austria for design achievement and an honorary Doctorate by Hong Kong Baptist University. He is honorary professor at the University of Hong Kong’s School of Architecture and at Hong Kong Polytechnic University’s School of Design. Steiner is co-author of ‘Cross-Cultural Design: Communicating in the Global Marketplace’ (Thames & Hudson 1995). A monograph, ‘Henry Steiner: Designer’s Life’, in Chinese, was published in 1999.

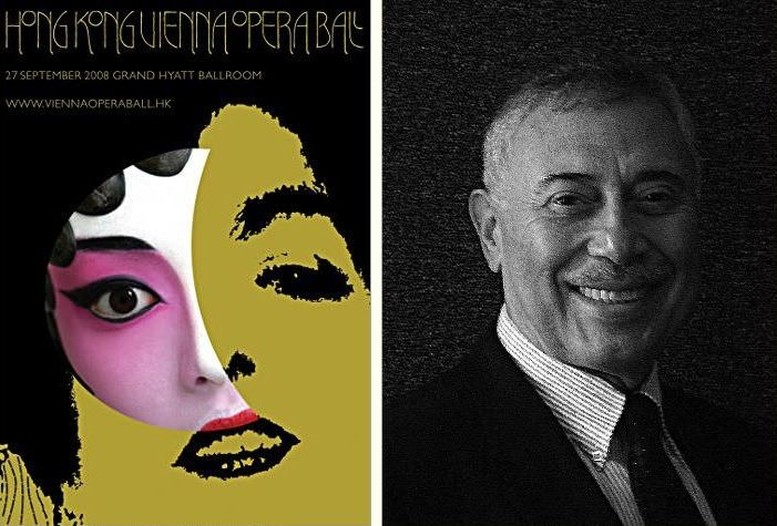

Henry Steiner, Ball Poster, 2008 Henry Steiner

Jianping He: I know you were born in Vienna, raised in the United States, then established your own design business in Hong Kong. For how long have you been living in Hong Kong? Do you see yourself as a Hong Kong designer?

Henry Steiner: I have lived in Hong Kong fifty years and just marked this anniversary with an exhibition of photographs in Hanart Gallery. I am a designer living and working in Hong Kong. In terms of “cultural citizenship” my sensibilities are broadly Euro/British.

Jianping He: What do you think about Hong Kong local designers? Have you ever been inspired by any of them?

Henry Steiner: Not in the sense that I was looking over my shoulder to see what they would do next.

Jianping He: You were a Graphic Design graduate at Yale University, taught by Paul Rand; what’s the impact of this professional education on your design career? Did it help you to perceive and adapt to Hong Kong’s local culture?

Henry Steiner: Rand had a profound impact, clarifying my vague notions about what it means to be a designer. I owe my career to Yale and especially to Paul. I retain a “modernist” inclination in my work. Paul taught the importance of ideas, research, function and contrast. These tools enabled me to practice design in Paris and New York prior to Hong Kong. I feel I can work anywhere since understanding local culture is the preparation for problem solving. (By the way, I adhere to a strict separation of design and self-expression, considering the latter to be “art”.)

Jianping He: Hong Kong is the marriage of British and Chinese culture and design must be bilingual. I think your understanding of the Chinese language is clearly revealed in your designs. How was this experience achieved? Have you been inspired by any Chinese designers or artists?

Henry Steiner: As above, understanding one’s cultural environment is essential prior to visual communication within that culture. It might also be noted that keen awareness of one’s surroundings is a genetic Jewish trait and one of the factors behind the survival of Jews. The artists to whom I especially relate are Ba Da Shan Ren, Chi Pai Shih and Wei Dong. Designers whose work I particularly follow are Xu Bing (I see him as more designer than artist) and Jiang Hua.

Jianping He: Apart from your use of Chinese characters, I notice you have a distinct sensitivity to Chinese culture. For instance, in your recent poster ‘Hong Kong Vienna Opera Ball’, you applied Li Bai’s poem “Jianjinjiu” in Chinese characters printed in clear varnish over the black background. This is an east and west integration, and shows a profound understanding of the culture. Do you believe that deeply beneath the national aesthetics and cultures of east and west there is much in common?

Henry Steiner: This poster was for a Vienna Opera Ball held in Hong Kong so I wanted to express some cross-cultural commonality. The idea is “Wein, Weib und Gesang” which led to Li Bai and Klimt sharing the same sheet of paper.

Jianping He: Have you encountered any difficulties in Chinese typography or typesetting? I noticed the collections in your studio and indeed in some of your work, you often use fonts like wood printing, kind of between digital text and Chinese calligraphy.

Henry Steiner: No problem. I use collage or, now, digital typesetting.

Jianping He: You are a western designer immersing himself in the east to integrate the two, while establishing your own design aesthetics and style. Can you share some of your experiences?

Henry Steiner: I have difficulty with your term ‘integrate’. As forcibly expressed in my book “Cross-Cultural Design,” I believe in contrast (thanks to Rand), and I dislike (or find boring) the concept of hybridization, or fusion.

Jianping He: The “integration” is actually based on an established understanding of different cultures, as you mentioned, “understanding one’s cultural environment is essential prior to visual communication in that culture”, under the concept of globalization designers have to understand different cultures.

Have you been inspired by German graphic design?

Henry Steiner: Among German nationals: Uwe Loesch, Pierre Mendell, Gunter Rambow. My other inspirations are “Germanic”: Herbert Leupin, Armin Hofmann, Jan Tschichold, Karl Gerstner, and especially Henry Wolf who had a very “weanerisch” sensibility.

Jianping He: What do you mean by “weanerisch”? And do you think there is any German influence on designs in Hong Kong?

Henry Steiner: It’s “weanerisch’” in the dialect pronunciation, i.e. “Viennese”. There was no real understanding or exposure to any kind of sophisticated graphic design when I arrived. It was mostly rather banal “commercial art”. There was no awareness until much later of, say, the Bauhaus – let alone the Wiener Werkstaette or post-war Swiss design.

Jianping He: In the postscript of Haruki Murakami’s novel “Norwegian Wood”, he said he wrote the novel in southern Europe. From this distance he had more sensitive and delicate thoughts about his homeland which aided his creativity. When I was designing so far from my roots I became more sensitive to my mother language, my homeland, the rivers, the mountains seen in the distance. Does a foreign environment benefit your creative work?

Henry Steiner: When you see yourself in a foreign mirror you become both alienated and more aware of what is distinctive in your formation. They say one learns a foreign language to better appreciate your own.

Jianping He: National identity and globalization seem to be opposing concepts. Whether Hong Kong or Berlin, graphic designers are slowly abandoning techniques from the 80s or 90s, such as brushes, pencils, darkroom, repro techniques etc. They embrace the convenience of computers and visualizing in universally available software, like Photoshop and Illustrator. Does this homogenize design as a consequence? Given this tendency, what will result?

Henry Steiner: I believe the phenomenon to which you refer is due to the digital revolution and goes well beyond the concerns of older graphic designers. We are all experiencing the most massive social upheaval since Gutenberg. Watching international protests, whether the Arab spring or American anti-capitalist demonstrations, I am struck by the uniformity of their placards, the common use of English, the sameness of their tweets and videos; even their manner of dressing is interchangeable. No question that national branding will be something artificially maintained only for the purpose of tourism. I get the feeling that, as with photographers and journalists, these are hard times for designers. Anyone who can use the appropriate software is able to turn out adequate decorations with no professional qualification required. And most clients are more concerned with price rather than quality.

I don’t believe that the design profession will become an extinct species but I do feel it is endangered. This is a fascinating, challenging time and I look forward to further developments. In the meantime I am grateful for the basic principles learned at school and from my early practice.

First published: hesign (publishing and design) (Ed.): DeSein. German Graphic-Design from Postwar to Present (1945-1990), Hong Kong 2011, (Interview p. 282-285).

Revised version for “Austrian Posters” by Henry Steiner.

With thanks to Steiner & Co for permission to publish this article on “Austrian Posters” and to René Grohnert for his help in this matter.