At the beginning of November 2016, the exhibition “Final Sites before Deportation” opened at Vienna’s Heldenplatz in the Outer Castle Gate, portraying the four deportation collection camps[1] for Jews. These little-known internment camps served as interim accommodation prior to deportation, until the victims were taken to Aspang train station in groups of 1,000 people. A total of 45 trains departed for the death camps between February 1941 and October 1942.

When the Book of the Dead for Maly Trostinec[2] was published in 2015, it revealed more detailed information on the tragic fate of Julius Klinger – besides Joseph Binder the most important Austrian graphic designer during the interwar period – and his wife Emilie.

At the age of 66, Julius Klinger was deported with his wife on 2 June 1942 to Maly Trostinec, near Minsk, together with 997 other people. “This consignment reached Minsk train station on Friday, 5 June, but ‘offloading’ only followed on Tuesday(!) of the following week. Until then, the coaches remained locked and the occupants received neither food nor drink. They were murdered directly after being ‘offloaded’ in Minsk and upon arrival in Maly Trostinec.”[3] The presumed date of death is 9 June 1942. Nobody survived this transportation, which was organised by the “NS Central Office for Jewish Emigration” in Vienna.

The Klingers had previously lived in a collection flat at Adlergasse 4, a historicist building with open courtyard (Pawlatschenhof) that was built in 1875 by Ferdinand Fellner and Hermann Helmer.[4] A total of 15 people were deported to Maly Trostinec from this house, and then murdered.[5]

During the preceding period, the life of Jews in Vienna had become increasingly restricted. From June 1938 they were no longer permitted to enter the city’s parks, from September 1939 they were forbidden to leave their houses after 8 p.m., and possession of radios was also prohibited. From May 1939 a new regulation enabled termination of rental contracts with Jews without notice. We do not know when the Klingers were forced to move to Adlergasse. In July 1940 Jews were forbidden to use telephones, and as of September they had to wear the Jewish badge. In September 1941 all typewriters and calculating machines, bicycles, cameras and binoculars had to be handed over, and in February 1942 Jews were forbidden to purchase newspapers and magazines. In March 1942 they were finally also banned from using public transportation.[6]

Portal Franz-Josephs-Kai 21 / Schellinggasse 6, (both photos: Christian Maryška, 2016)

During the period following “annexation”, Klinger desperately attempted to continue working. At the end of May 1938 he placed an advertisement in the “Zionistische Rundschau” newspaper.[7] He offered lessons in advertising and commercial art, with his name – which was well-known in specialist circles – highlighted in bold. At the same time, between April and October 1938 he taught “courses in commercial art” in his studio, with support from his long-standing friend and architect Rudolf Hönigsfeld in the subjects of shopfront construction, shop window decoration and exhibition construction.[8] It is not known how many people responded to this advertisement. The address where Klinger lived and worked for many years between the wars – Vienna I, Schellinggasse 6[9] – appeared for the last time in Adolph Lehmann’s Allgemeiner Wohnungs-Anzeiger in 1939.

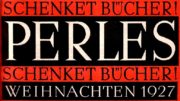

Advertisement in the Zionistische Rundschau, dated 27 May 1938

One of probably the last posters, if not the final poster, that was designed by Julius Klinger at the end of 1937/beginning of 1938, is an impressive 12-sheet poster (250 x 278 cm) for Ankerbrot, an industrial bakery in Vienna. Huge numbers announce the new year 1938 in Klinger’s seasoned, down-to-earth and modern style, without focusing visually on a specific product. This poster was used by a strong brand that hoped to attract customer loyalty in the new year as well. The effect on today’s observer is entirely different than was intended by the designer and company. We naturally know that in 1938 Austria was “annexed” to Hitler’s German Reich and thus directly and indirectly, the fate of the Jews was sealed, and we know about the suffering that was to be faced by Julius Klinger. The company Ankerbrot was taken over and Aryanised by the National Socialists immediately after “annexation”, and at the same time the monogram “HFM” was removed from the company logo, which stood for the company founders Heinrich and Fritz Mendl. Newspaper advertisements announced: “As of 15 March 1938 the Anker Bread Factory (Ankerbrotfabrik AG) has purely Aryan management and employs 1,600 Aryan employees.”[10].

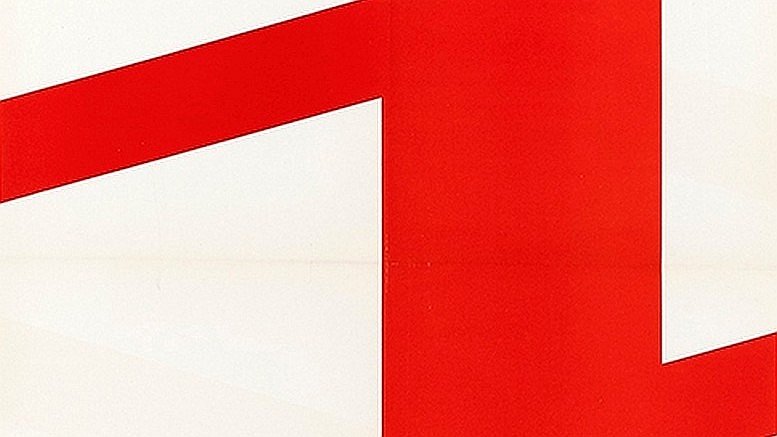

Poster by Julius Klinger, 1937, © Austrian National Library

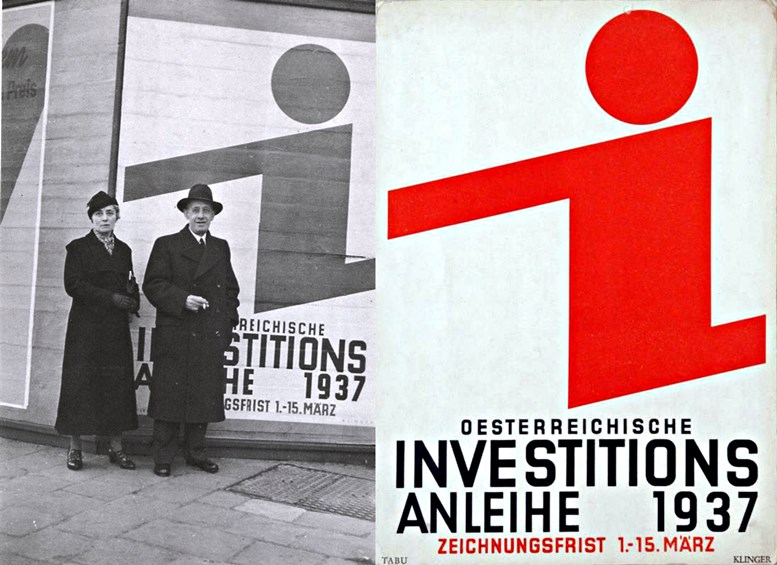

In the final year of freedom and independence in Austria, Julius Klinger designed another very down-to-earth and uncluttered poster that was commissioned by the state, for the Austrian Investment Bond in 1937. The main objective of the investment bond was to improve the infrastructure, specifically electrification of the federal railway and the expansion of federal roads, in a similar way to the Austrian Lottery Bond in 1933 and the Austrian Labour Bond in 1935 for which Julius Klinger had also designed poster motifs – all using the colours red and black: a masterpiece in the use of limited resources. A final photo of Julius Klinger at the age of 60 is also documented in connection with this poster, showing him with his wife Emilie at the beginning of 1937 in front of a billboard with his large-format investment poster. Looking confidently at the camera, with a cigarette in his hand and dressed in elegant winter clothing, it looks as if he is being typographically embraced by his “i”, which could also symbolise a bond purchaser.

Left: Photo of the Klingers, 1937, © MAK / Right: Poster “Austrian Investment Bonds, 1937”

The final exhibition of Julius Klinger’s works during his lifetime took place – an irony of fate – in the capital city of the National Socialist German Reich. The photo of him standing in front of the investment bonds poster in Vienna was taken at exactly the same time as an exhibition titled “The Jewish Poster” was being held in Berlin, where he had been active for many years. At the beginning of 1937 the Jewish Museum displayed posters by Jewish artists from the collection of Hans Sachs, the most important German poster collector in the first half of the 20th century. In addition to works by Lucian Bernhard, Louis Oppenheim and Paul Leni, Julius Klinger’s posters from his Berlin period before the First World War were also on view.[11]

Translation: Rosemary Bridger-Lippe

[1] Dieter J. Hecht, Eleonore Lappin-Eppel, Michaela Raggam-Blesch: Topographie der Shoah. Gedächtnisorte des zerstörten jüdischen Wien. Vienna 2015.

[2] Waltraud Barton (ed.): Maly Trostinec – Das Totenbuch. Den Toten ihre Namen geben. Vienna 2015.

[3] Ibid. p. 115.

[4] Cf. https://www.memento.wien/address/1/ (20.11.2016). The house was badly damaged when it was hit by a bomb in 1945, and it was rebuilt in 1958/61 facing the embankment. Present address: Franz-Josephs-Kai 21.

[5] Ibid. p. 264.

[6] Chronology in the exhibition “Final Sites before Deportation”.

[7] Issue dated 27 May 1938. It was published between 20 May 1938 to 4 November 1938, from 3 February 1939 it was succeeded by the “Jüdische Nachrichtenblatt – Ausgabe Wien” until 4 June 1943.

[8] Letter of recommendation from Julius Klinger, dated 3 March 1939. Wienbibliothek.

[9] This thoroughly historicist house was built by Ludwig Tischler in the year when the World Exhibition took place in Vienna, in 1873.

[10] Christian Rapp, Markus Kristan: Ankerbrot. Die Geschichte einer großen Bäckerei. Vienna 2011, p. 76.

[11] Olga Bloch: Das jüdische Plakat. Zur Ausstellung des Berliner Gemeinde-Museums. In: Central-Verein-Zeitung. Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums, dated 4 March 1937, p. 6. In the following year the poster collection was seized by the Nazis and Hans Sachs emigrated to the United States.