“Any artist who wishes to work in the world of advertisements must be an experienced, versatile expert in the practicalities of real life who is a master of his craft and also capable of fully acknowledging and comprehending the business intentions behind commercial undertakings.” These are the words of Julius Klinger, who understood how to create works that responded to the demands placed on an advertising artist.

Born in Vienna on 22 May 1876, he received technical training at the TGM technical college in his native city. He was given instruction in subjects such as commercial technical drawing, which evidently later influenced his precise style of illustration as an artist and multi-talented graphic designer.

In 1894 Julius Klinger started to work for the Viennese fashion magazine “Wiener Mode”. Assignments as an illustrator for the art and satirical magazine “Meggendorfer Blätter” were secured for him by Kolo Moser, and he moved to Munich in 1896 for this purpose. In 1897 he relocated to Berlin, where he worked for another satirical weekly entitled “Lustige Blätter”. He designed his first poster in the same year, for “Das kleine Witzblatt”.

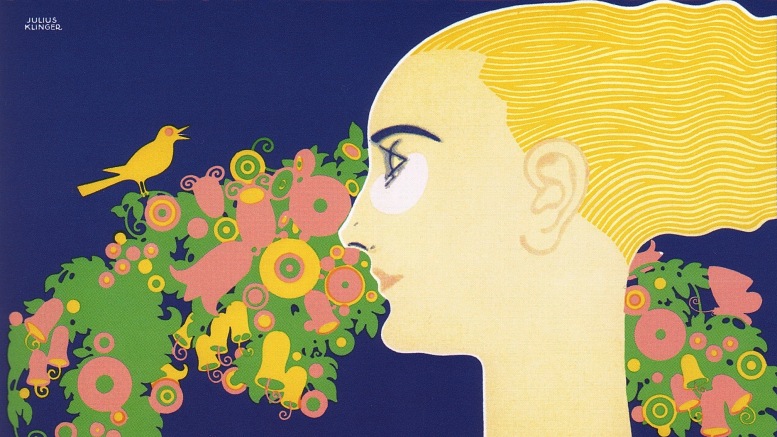

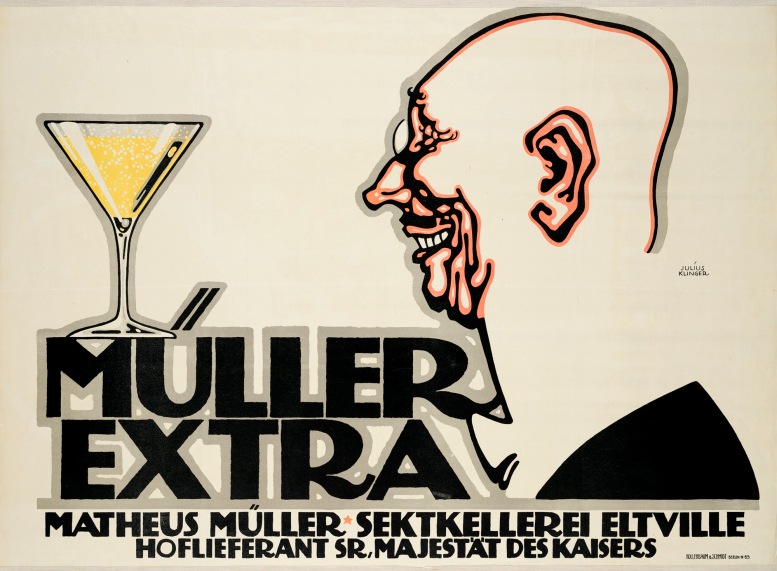

Poster, Berlin, 1912

Klinger’s early works were influenced by ornamental Jugendstil and were highly successful. He offered source material for architects, illustrators and applied arts in two books of samples focusing on the woman “in modern ornamentation” (im modernen Ornament) and one album on grotesque drawings (Die Grotesklinie). However, he would soon leave art nouveau behind and develop a more reduced style. Klinger joined a group of young designers, who also included Ernst Deutsch(-Dryden), to develop new and professional poster designs for the Berlin printers “Hollerbaum & Schmidt”. He remained in Berlin for almost two decades, during which he created (as he later recalled) “several thousand reproduced works for trade, industry and commerce”.

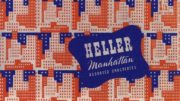

Poster, Berlin, 1912

At the beginning of the First World War, Julius Klinger was recalled to Vienna for military service. When the war ended, he remained in Vienna and opened a studio. Despite the tense economic situation, he received plenty of interesting work: for example, the Austrian National Bank commissioned him with the “publicity management and production of all printed materials”, and the promotional campaign developed by him for Tabu cigarette paper in 1919 was on a scale that was previously unknown in Vienna. Besides advertisements and posters, the full expanse of house walls was used. He also repeatedly returned to book design and illustration.

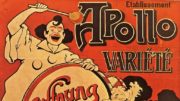

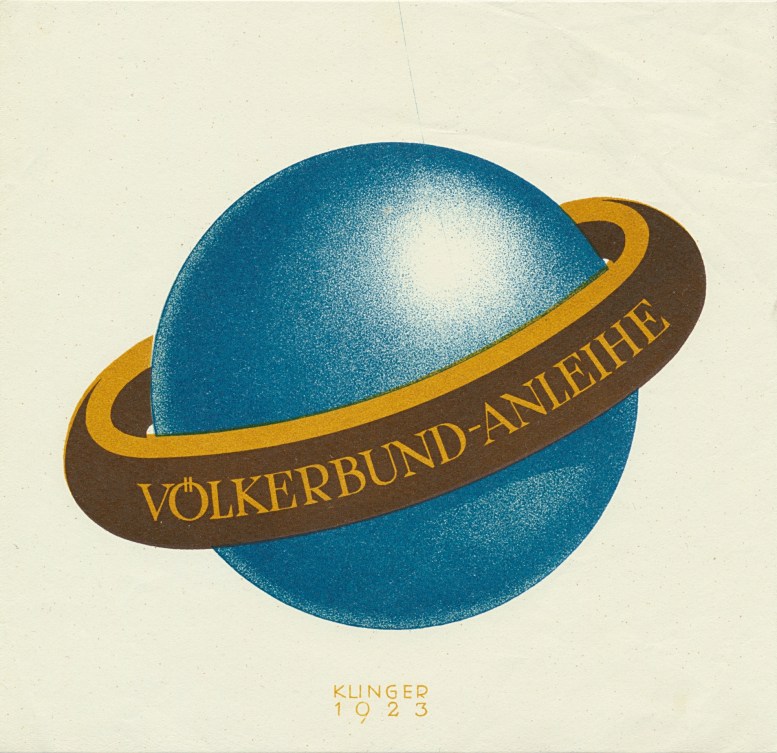

Poster, Vienna, 1923

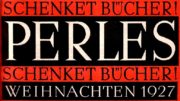

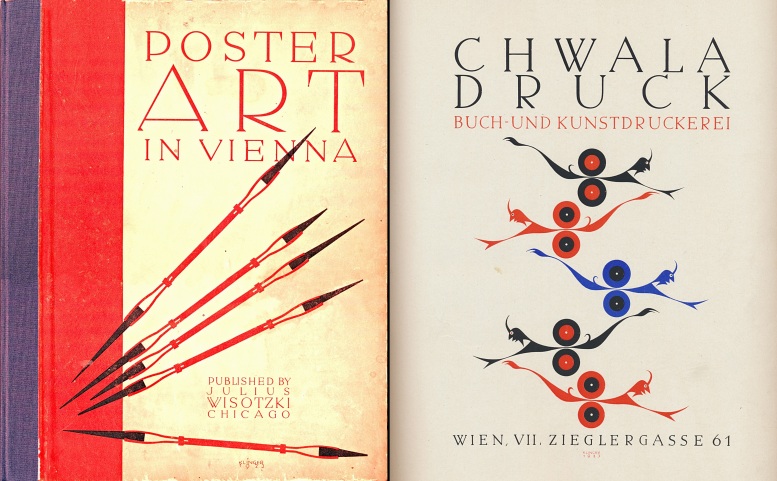

In the 1920s the colours and shapes in Klinger’s work became even more reduced – purely typographical solutions were a frequent choice. In 1923 Julius Klinger joined forces with pupils and colleagues to publish a book of samples entitled “Poster Art in Vienna” for this new kind of functionalist advertising. In addition to Klinger’s works, it included designs by Hermann Kosel and Wilhelm Willrab, among others, and was intended for the English-language market.

Poster Art in Vienna, Chicago, 1923

In December 1924 Julius Klinger held a major lecture in Vienna’s Konzerthaus on the subject of “The Chaos of the Arts” (Das Chaos der Künste), which he also published in a separate little book. Displaying a marked influence by Adolf Loos, Klinger once again showed his love of the US: “We, a small native Viennese group who – despite their living in this city – do not want to renounce cosmopolitan life, fondly hope for the following: we wish that old, tired Europe would recover with the help of buoyant AMERICAN qualities. We are wholeheartedly fulfilled by our belief in our era. We are able to clearly recognise the pure style that this era owes to the progressive mechanisation of the world, and we feel the inner, full substance of this epoch without succumbing to a rosy pseudo-idealism as a result.”

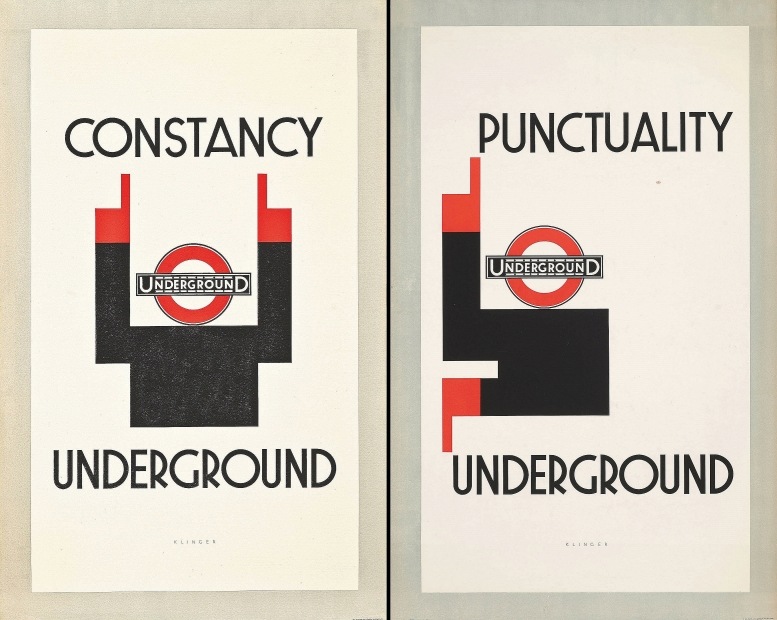

Posters, London, 1929

Nonetheless, following a lengthy trip to the US in the years 1928/29 Klinger returned to Austria in disappointment, whereas posters commissioned for the London Underground gained him remarkable international success in 1929.

After the annexation of Austria by National Socialist Germany in 1938, Julius Klinger was barred from working as he was a Jew. On 2 June 1942 he and his wife Emilie were arrested, deported to Minsk, and probably murdered shortly afterwards. Thus, Klinger is among the group of people who were not only physically destroyed by the National Socialist terror regime, but for a long time were also robbed off the rightful recognition and appreciation of their works.

Translation: Rosemary Bridger-Lippe