Blumenverkäuferinnen, Schuhputzer, Straßenkehrer – und auch Plakatierer, Schildermaler und die sogenannten Sandwich-Men mit ihren an Brust und Rücken festgeschnallten Werbetafeln gehören zu jenen Typen aus dem Londoner Straßenleben, die John Thomson und Adolphe Smith 1877 in den Mittelpunkt einer vielbeachteten Reportage stellten. Die beiden hatten ein klares soziales Anliegen: nämlich auf die Armut sowie die oft schwierigen Arbeitsbedingungen jener Menschen aufmerksam zu machen, die im täglichen Leben der Großstadt viele als selbstverständlich erachtete, jedoch kaum entsprechend gewürdigte Dienste leisteten.

Ihr Projekt setzten Adolphe Smith und John Thomson in einer 36-teiligen Dokumentation um. Unter dem Titel „Street Life in London“ erschien diese zunächst, ab Februar 1877, in zwölf Einzelheften, von denen jedes drei verschiedene Impressionen aus dem Straßenleben enthielt. Noch im selben Jahr kam die gesamte Serie auch in Buchform heraus, bald folgten weitere Ausgaben. Jeder der 36 Abschnitte besteht aus einem Text und einer Fotografie, wobei, wie Smith und Thomson im Vorwort zur Buchausgabe betonten, den Fotos als objektiven Belegen besondere Bedeutung zukam: „The unquestionable accuracy of this testimony will enable us to present true types of the London Poor and shield us from the accusation of either underrating or exaggerating individual peculiarities of appearance.“[1]

Alle 36 Fotos hatte John Thomson (1837–1921) aufgenommen, ein versierter und erfolgreicher Fotopionier, der vor allem durch die vielen Aufnahmen, die er in den 1860er Jahren bei ausgedehnten Reisen in Asien gemacht hatte, berühmt geworden war. Thomson verfasste auch einige der Texte für „Street Life in London“, der Großteil aber stammt von Adolphe Smith (1846–1924). Im Gegensatz zu Thomson war er, als die Reportage erschien, relativ unbekannt, machte sich aber in der Folge mit zahlreichen Publikationen und vor allem auch durch sein vehementes sozialistisches Engagement einen Namen. Gemeinsam schufen Smith und Thomson eine frühe und für viele folgende Arbeiten beispielgebende Sozialreportage, über die der Thomson-Biograf Richard Ovenden vermerkt: „The reason Street Life has ultimately succeeded as the first social documentary photography is […] that its primary aim was to inform: it was never the intention of Smith or Thomson to claim the literary and artistic high ground […] Rather, they aimed to transfer the experiences of the poor into the homes of the comfortable middle class, and to make them aware of a different, harsher reality“[2].

„The London Boardmen“ aus dem Band „Street Life in London“, 1877. Die Schilder am Körper und auf dem Hut des Sandwich-Man werben für das Pflegemittel „Renovo“, das für Handschuhe verwendet wurde

Zu jenen, die in der harten Realität des Londoner Straßenlebens besonders vielen Demütigungen ausgesetzt waren, gehörten die „London Boardmen“ – jene Sandwich-Men, die als lebende Werbeflächen unterwegs waren und deren Tätigkeit sehr gering geschätzt wurde. Durch ihre Adjustierung waren sie in ihrer Bewegungsfreiheit stark eingeschränkt und konnten sich daher auch kaum gegen die zahlreichen Attacken, denen sie ausgesetzt waren, wehren – nicht dagegen, von Kindern mit Schlamm bespritzt zu werden, von offenen Omnibussen aus Tritte gegen die Werbetafeln erdulden zu müssen oder von vorbeifahrenden Kutschern Peitschenhiebe zu erhalten.

Rekrutiert wurden die Boardmen über spezielle Agenten, denn: „A business firm, advertising on a large scale, could not incur the trouble of enlisting the band of boardmen. The organization, the superintendence, and payment, etc., of these men is a business in itself, and the intermediary is, therefore, almost indispensable. Boards have to be purchased, the correct advertisements pasted on them, the men must be enrolled, started at a fixed hour, and above all carefully watched, or they would simply deposit the boards in a corner.“[3] Als Tageslohn erhielten die Boardmen bestenfalls 18 Pence[4], oft auch weniger: „Their hours, it is true, are short, that is to say from ten to five in winter, and ten to six in summer; but they must be constantly on the move during the whole of this time, and their employment is far from regular.“[5]

Es gebe, so Adolphe Smith, der den Text verfasst hat, keine andere Berufsgruppe, die in ihrer Zusammensetzung so heterogen sei wie jene der Boardmen: „Unlike many other street trades, this business is not followed by a special tribe. […] boardmen are of all sizes, ages, shape, and complexion. Some are hopelessly vulgar and ignorant, others have received the education of gentlemen. They represent, to use a consecrated expression, all who have ‚gone to the wall‘. Any one who is temporarily in difficulties may offer to carry boards. Others, who are permanently incapable of helping themselves, live on, year after year, contentedly bearing this simple burden.“[6]

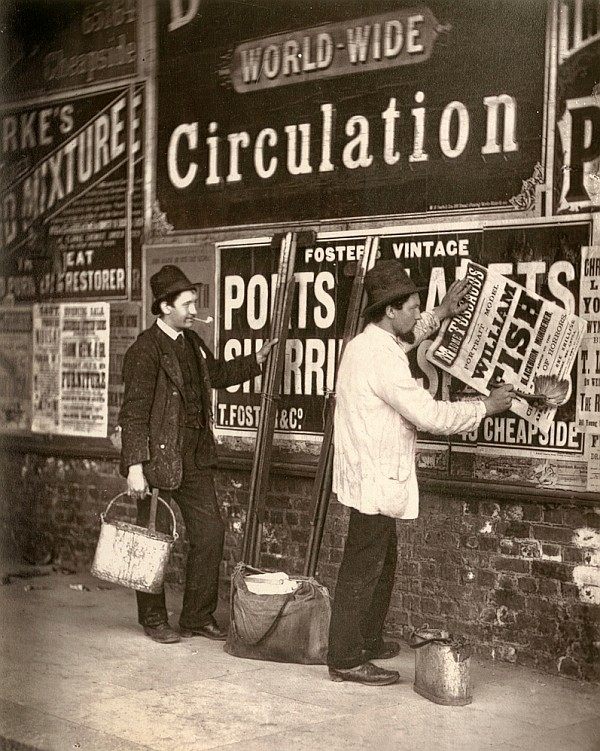

„Street Advertising“ aus dem Band „Street Life in London“, 1877

Im Gegensatz zu den Boardmen hätten die Plakatierer, so Adolphe Smith, ein deutlich ausgeprägtes Standesbewusstsein. Dies hänge auch damit zusammen, dass das Affichieren einiges an Übung und Können verlange und eine durchaus angesehene Arbeit sei: „As a rule, also, when once a man has become proficient in the art of bill-pasting, he rarely abandons this style of work. Nor is it quite so easy as it may seem. There is a certain knack required in pasting a bill on a rough board, so that it shall spread out smoothly, and be easily read by every pedestrian; but the difficulty is increased fourfold when it is necessary to climb a high ladder, paste-can, bills, and brush in hand. The wind will probably blow the advertisement to pieces before it can be affixed to the wall, unless the bill-sticker is cool, prompt in his action, and steady of foot. Thus the ‚ladder-men‘, as they are called, earn much higher wages, and the advertising contractors are generally glad to give them regular employment.“[7]

Rund 200 Plakatierer hatten in den 1870er Jahren, wie Smith für seine Reportage recherchierte, in London eine dauerhafte Anstellung. Bei guter Auftragslage und bei besonderen Anlässen, bei denen ein kaufkräftiges Publikum anwesend war, wurden noch weitere „bill-stickers“ temporär beschäftigt. Deren Aufgabe bestand sehr oft im „fly-pasting“, also im Wildplakatieren: „It consists of sending men out to certain distances, either on foot or with a cart and van, to post bills indiscriminately wherever they can find a convenient spot which is not let to, and reserved by a contractor.“[8] Viel zu tun hatten die Wildplakatierer, wenn Pferderennen stattfanden, und vor allem auch, wenn auf der Themse die traditionelle Ruderregatta der Universitäten Cambridge und Oxford ausgetragen wurde: „They often start at two in the morning on the day of the race and paste their bills up all along the road. But rival bill-stickers soon make their appearance, and the paste of one bill is hardly dry before another one is daubed over it. Thus the contractors have to send out a fresh batch of men a few hours later to paste each other out. For instance, a firm in Soho assured me that they sent out men on the boat-race day at two in the morning, then at six oʼclock, again at eight, and finally at ten, with orders to paste their bills over all other advertisements.“[9]

Der Wert einer Anschlagfläche sei, so Smith, „absolutely fabulous“, denn für die Anmietung von Plakatwänden würden vielfach Rekordpreise bezahlt: „Indeed, so much money is made in this way, that there are certain houses standing in conspicuous places by the railway lines, which are not pulled down, though in ruins, because it pays the owners better to let the outside walls for advertising than to let the interior for dwelling purposes.“[10]

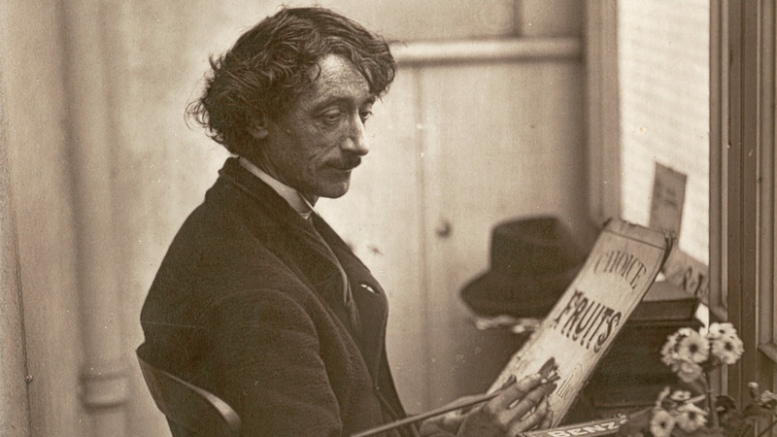

Neben Berichten über die Situation verschiedener Berufsgruppen finden sich in „Street Life in London“ auch Porträts einzelner Persönlichkeiten, wie etwa eines Schuhputzers, eines Kutschers und eines Straßenclowns. Es sind Persönlichkeiten, die Smith und Thomson aufgrund ihrer Eloquenz oder durch ihr ungewöhnliches Schicksal besonders aufgefallen sind. So etwa „‚Tickets‘, the Card-Dealer“, ein Schildermaler, der wie Adolphe Smith schreibt, „comes straight from the ‚centre of civilization‘“[11]. Denn der Mann mit dem Spitznamen Tickets stammte aus Paris, wo er zunächst im Textilhandel tätig gewesen war, dann als Freiwilliger zur Armee ging, jedoch wegen seiner schwachen Gesundheit bald wieder entlassen wurde. Sein weiterer Weg führte ihn in die USA, wo er eine typische und durchaus erfolgreiche Einwandererkarriere machte: Er begann in San Francisco als Tellerwäscher, war dann Nachtwächter, später Französischlehrer und schließlich Buchhalter und Übersetzer in einem New Yorker Hotel. Doch Heimweh, „fatal to so many emigrants“[12], beendete diese Laufbahn. Tickets kehrte nach Europa zurück, landete in England und blieb – aufgrund der unruhigen politischen Lage im Frankreich der Zweiten Republik und auch aus Geldmangel – in London hängen. Seinen kärglichen Lebensunterhalt verdiente er dort zunächst als Claqueur in einem Theater, dann als Schildermaler: „From morning till night he wanders about, looking into the windows of small shops, till he discovers a ticket of dingy appearance, stained in colour, dogʼs-eared, bent, and altogether disreputable. With eagle eye all these defects are discerned, and ‚Tickets‘ enters boldly into the shop, to press on the tradesman the advisability of purchasing a new ticket. He undertakes to supply a precise copy of the old and worn announcement on a better piece of cardboard, freshly painted, or, perhaps, more elaborately ornamented.“ Es ist ein Gewerbe, das nicht allzuviel einbringt, vor allem, weil der Geschäftsverlauf sehr wechselhaft ist: „Cards are only required in fine weather, when pedestrians loiter about, and there is a better chance of tempting them by startling announcements affixed to the goods in shop windows. Nevertheless the hero of this chapter is still buoyed by sanguine expectations. He hopes that the number of his customers will gradually increase and that he will be able to save on his earnings. Then, like a true Frenchman, he will return to France“[13].

[1] Smith, Adolphe u. John Thomson: Street Life in London. New York, Reprint 1969, Preface.

[2] Ovenden, Richard: John Thomson (1837–1921). Photographer. London 1997, S. 88.

[3] Smith, Adolphe: The London Boardmen. In: Street Life in London, S. 99.

[4] Das war ungefähr ein Viertel von dem, was ein Maurer um 1880 in London pro Tag verdiente. Vgl. Bowley, Arthur L.: Wages in the United Kingdom in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge 1900, S. 63.

[5] Smith, Adolphe: The London Boardmen. In: Street Life in London, S. 99f.

[6] Ibid., S. 100.

[7] Smith, Adolphe: Street Advertising. In: Street Life in London, S. 36.

[8] Ibid., S. 38.

[9] Ibid., S. 38.

[10] Ibid., S. 38.

[11] Smith, Adolphe: ‚Tickets‘, the Card-Dealer. In: Street Life in London, S. 59.

[12] Ibid., S. 60.

[13] Ibid., S. 61f.