“After a long break, the Perles bookshop is starting to organise graphic exhibitions again. It is to be warmly welcomed that it is starting with young people. First of all, we have a debut”, noted the renowned Viennese art critic Wolfgang Born in the fall of 1932, referring to the debut of the young graphic artist Lizzi Pisk: “Lizzi Pisk is actually a dancer. But she also learned to draw. Now she combines these two seemingly distant fields. The result is quite original and pleasing. The transition from dancing to drawing is formed by costume designs. First of all, they have the advantage of being the result of an intimate knowledge of the task – which is rarely the case with a painter alone. But secondly, they are tasteful – and that is a matter of talent.”[1]

The multi-talented and later internationally successful artist Alice Pisk was born on 22 October 1909 in Vienna’s 2nd district, Lessinggasse 8. Her Hebrew first name, Reisel, is also recorded in the birth register of the Jewish Community of Vienna.[2] Apparently in memory of this, Alice Pisk later sometimes used Therese, the German equivalent to Reisel, as a middle name. During her time in Austria, Pisk preferred the name Lizzi, which later became Litz in Great Britain. The reason for this change can be found in a letter to the Austrian author Hans Weigel, in which she wrote on stationery with the letterhead “Litz Pisk”: “Why I have been called as above for 30 years is complicated. (Lizzi is pronounced here with a soft z & comes from Elizabeth) (Alice Therese, A.T.P. or L.T.P. is for documents, bank, etc.).”[3]

Her parents were Anna, née Karpeles (1877–1928), and Sigmund Pisk (1867–1933). Both came from the Weinviertel region in Lower Austria.[4] Alice grew up as the youngest of four children, with three brothers in a well-off, middle-class Jewish family in Vienna. Her father, together with his brother Gustav, owned the dairy company “Brigittenauer Molkerei” in Vienna’s 20th district, at Nordwestbahnstraße 71. The company played a considerable role in supplying the Viennese population with fresh milk and dairy products such as butter, cream, sweet cream and yoghurt. In 1926, for example, no fewer than 343 shops in Vienna were supplied by it.[5]

The Brigittenau Dairy Building, Neuigkeits-Welt-Blatt, 27.6.1926

In keeping with her creative talents, Lizzi began studying at the Vienna School of Applied Arts (now the University of Applied Arts) at the age of 15, i.e. in 1924. She began as a pupil of Franz Čižek, who specialised in working with children and young people, where she learned “General Theory of Forms”, and she studied “Ornamental Lettering and Heraldry” with Rudolf Larisch.[6]

Čižek’s many years of activity at the School of Applied Arts led to corresponding international successes, especially in the mid-1920s. The works of his class were presented in the Netherlands in 1922 and in a travelling exhibition in the USA in 1923 and 1924.[7] Influenced by Cubism and Futurism, Čižek’s own Viennese interpretation of the then current styles had emerged in his classes – the so-called Kineticism. In the same year Lizzi Pisk started at the School of Arts and Crafts, Franz Čižek explained his work as a teacher to the faculty: “My previous work is much misunderstood, as my department is a purely rhythmic one. I had to distance myself from ornament in the narrower sense. It is tiring to always produce patterns. […] I have therefore made my school a rhythmic one, in the conviction that rhythm is the basis of all arts and crafts. The study of nature can never be the determining factor in the creation of ornamental forms. I have said to myself that rhythm cannot be obtained from old formulas, but from life.”[8]

This statement by Čižek also fits perfectly with the artistic lifetime achievement of Litz Pisk, who managed to harmoniously combine her graphic talent with her talents in dance and acting.

In 1926/27, Pisk took the course “Drawing and Shaping from the Human Figure” with Erich Mallina.[9] She later recalled: “During this period I also began to feel that the imposed stillness of the model in a conventional life drawing class interested me less than the human body in action or at rest. At the same time I joined in classes of all sorts related to movement – Laban, ballet, folk, national and even acrobatics. So full of these ideas and experiences, I finally started my studies with Strnad.”[10]

Oskar Strnad was not only an important architect in the interwar period, but also a successful stage designer. He taught at the School of Arts and Crafts, where Litz Pisk studied with him in the architecture class in 1927/28.[11] Strnad was also a prominent member of the teaching staff at the Reinhardt Seminar, a renowned school of drama in Vienna. Pisk was then a guest student in Strnad’s stage design class[12] from October 1931 to June 1932.[13]

Another important person for Pisk’s artistic development was the famous dancer and choreographer Hilde Holger, who had founded a “School for the Art of Movement”[14] in 1926 and, together with Grete Kollmann, ran the “New School for the Art of Movement” from 1927.[15] Pisk had first been Holger’s student[16] and then, from September 1928[17] to May 1929[18], co-owned the “Neue Schule für Bewegungskunst” together with Hilde Holger. However, she soon became self-employed as a teacher and opened her own “School for Gymnastics and Artistic Dance”[19] on 1 October 1929, which was officially approved by the Vienna City School Board in December 1929 as a “Private School for Gymnastics and Artistic Dance, and for Ornamental and Figural Drawing”[20].

During these years, Pisk also began to establish herself as a costume designer: She designed the costumes for a dance production by Hilde Holger[21] as well as for a comedy production by the “Neues Wiener Schauspielhaus”[22]. And she published her first works as an illustrator: For the “Children’s Afternoons” arranged by the young actress Edith Dorn, Pisk designed a slide show that had “A Merry Fairy Tale Journey to England” as one of its themes.[23] In 1930, she designed the cover of the Berlin journal “Der Tanz”[24], and from 1931 she was able to contribute her unmistakable caricatures to the popular Viennese illustrated magazine “Die Bühne”.[25]

The year 1932 was a highlight in the early career of Lizzi Pisk, who was only twenty-two at the time. In April, the Vienna premiere of the opera “Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny” by Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht took place at the Raimundtheater.[26] Hans Weigel, later well-known as an author and theatre critic, was a friend of Lizzi Pisk’s brother Gerhart and responsible for organising the project[27], while Lizzi was entrusted with designing the stage set, which she created in a radically minimalist way. Weigel later recalled that she “made the decorations, which essentially consisted of three poles of different lengths.

Lizzi Pisk, at that time the full-time head of a gymnastics school, but also a listener at the Reinhardt Seminar, an ingenious all-rounder, has been a good friend of mine ever since, even though she has long since lived in Great Britain. She is a director, designer, choreographer and much more, we correspond with each other through the decades and see each other as often as we can (rarely enough anyway). She was my first interlocutor at the gateway to the world of theatre, she took me from being an interested dilettante one step further into the profession. I went to dress rehearsals and theatre performances with her and gradually learned to know what I was talking about when I talked about theatre. In that spring of 1932 I had got to where I have been ever since: to the theatre.”[28]

The renowned composer and critic Joseph Marx wrote about the premiere of “Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny”: “The stage design corresponds to the work: primitive stylisation of the idea. With great skill Lizzi Pisk knows how to get all kinds of effects out of a few curtains, boxes and poles.”[29] “Das interessante Blatt” summed up in a similar vein: “Good in their primitiveness and effect are Lizzy[!] Pisk’s stage designs.”[30]

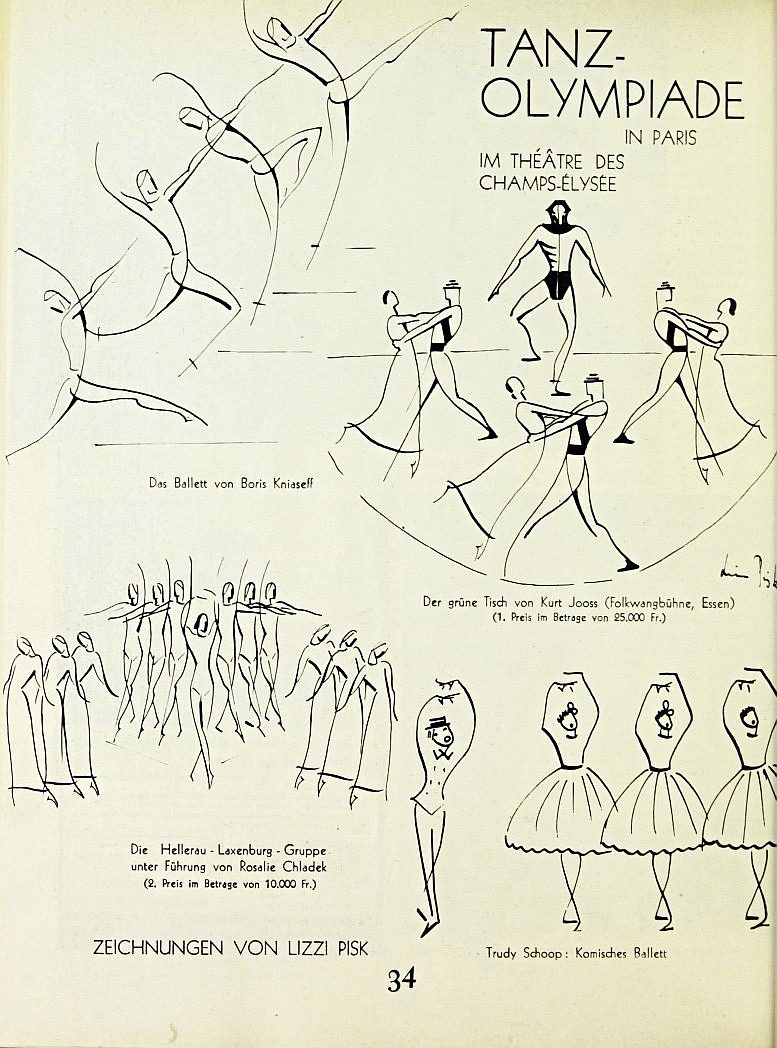

After that, Pisk became increasingly involved with costume designs again: For example, the Viennese dancer Lisl Rinaldini wore costumes by Lizzi Pisk during a successful performance at the Vienna Urania.[31] Lizzi Pisk also designed the costumes for the production with which the troupe of the Austrian choreographer Gertrud Bodenwieser won international recognition at the newly founded “Concours de Choréographie en Souvenir de Jean Borlin” in Paris in 1932.[32] The first prize was won by Kurt Jooss with his troupe from the Essen Folkwang School, second place went to the Austrian choreographer Rosalia Chladek with the Hellerau-Laxenburg-Schule, and Bodenwieser’s production with the costumes by Pisk[33] was awarded a bronze medal[34].

We can confirm the general consensus that Lizzi Pisk was personally present in Paris[35] based on a pictorial report drawn by her for the magazine “Die Bühne”.[36] In connection with the dance competition, an exhibition of costume designs and stage models was held in Paris at the “Galerie la Renaissance”, where “dessins de danse de Lizzi Pisk” were also presented.[37]

“Dance Olympics in Paris”, Die Bühne, 1932 8/1 (Austrian National Library, ANNO)

The artist’s first solo exhibition in Vienna followed in the fall of 1932. It took place in the prominent Viennese bookshop Perles[38]. A letter recently acquired in a Viennese antiquarian bookshop documents the conditions under which Lizzi Pisk was able to exhibit and also sheds light on the working situation of young Austrian artists in those years. On 5 September 1932, Pisk wrote to the bookseller Moritz Perles: “In reply to your letter of the 2nd of this month, I confirm that I will open an exhibition of my drawings (costume pictures and caricatures) in your exhibition space in mid-October.

The invitations and their dispatch will be at my expense, while you will kindly provide me with the exhibition space free of charge. You will receive half of the proceeds from the drawings sold. I will discuss the selling price of the drawings, as well as the window posters, with you verbally in due time.” Pisk also informed the bookseller that she had not yet received her work back from the Parisian exhibitors: “I have given the Parisian dance archives the last deadline with the 10th of this month.”[39]

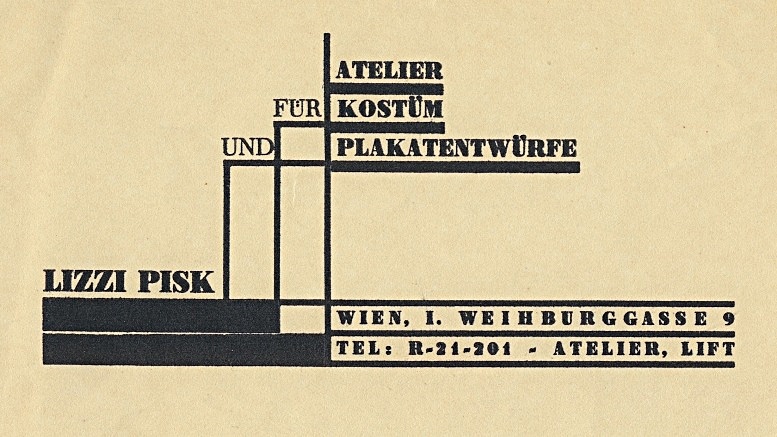

Letterhead, 1932 (private archive)

It can be assumed that the very modern letterhead, reminiscent of the Bauhaus style, was designed by Pisk herself. The text “Atelier für Kostüm und Plakatentwürfe” – “Studio for costume and poster designs” – proves that the young artist also wanted to expand her activities in the field of commercial graphics. However, no posters designed by her at that time have yet been found. But that Pisk was serious about pursuing commercial graphics as a profession is proven by the fact that she joined the “Bund Österreichischer Gebrauchsgraphiker” (Association of Austrian Graphic Designers) in 1932. She was thus one of the first women in Austria to belong to this association.[40] However, Pisk apparently did not receive any commissions, although the quality of her graphic work was praised by experts: In addition to the art expert Wolfgang Born quoted at the beginning, the art critic of the “Wiener Tag” was also fascinated by the young artist’s independent style: “Her speciality is artistic, not to say kinetic caricature. She captures dancers and actors with particular love. In a kind of futuristic expressionism. Often a few characteristic lines or sparse shadowy stripes are enough for her to reproduce the essence of what she sees; unimportant things always fall by the wayside. Many things appear as if they were drawn wire sculptures. Lizzi Pisk definitely has theatre blood, which is also revealed by her striking puppets. By the way, her Mahagonny decorations have already revealed that.”[41]

Advertisement in the daily newspaper “Die Stunde”, 29.10.1932 (Austrian National Library, ANNO)

In a short report in the daily newspaper “Die Stunde” it says about Lizzi Pisk’s exhibition in Vienna: “It is an astonishingly versatile talent that one gets to know better here: besides scenic designs and figures, there are particularly lively sketches of well-known stage artists and finally some very effective poster designs. The vividly executed stage models for the imaginative production of Brecht-Weill’s opera ‘Mahagonny’, which was produced with the simplest of means, are also of particular interest.”[42]

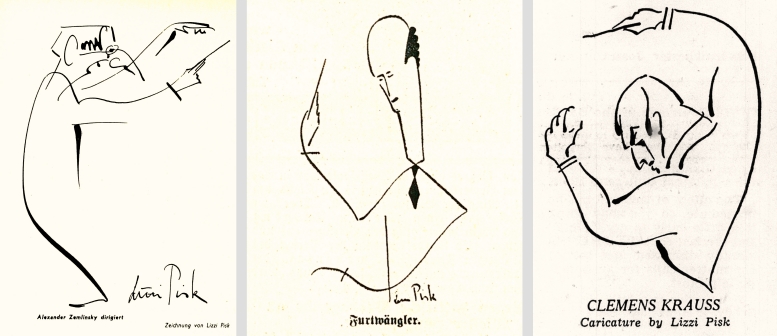

The exhibition at the Perles bookshop apparently also featured caricatures that Pisk had already published in newspapers and magazines. From September 1931, she occasionally placed caricatures in the illustrated magazine “Die Bühne”[43], and from the fall of 1932 she also received commissions from the daily newspaper “Der Wiener Tag”. For the latter, she regularly created caricatures of well-known protagonists of Viennese musical and theatrical life in her unmistakable, very own grotesque style.[44] In its October 1932 issue, the fashionable illustrated magazine “Moderne Welt” also featured caricatures by Pisk on the Viennese cultural scene.[45]

Pisk was obviously also interested in the pantomimic quality of conducting. From left to right: Alexander Zemlinsky, Die Bühne. 1933 11/1 (Austrian National Library, ANNO), Wilhelm Furtwängler, Der Wiener Tag, 19.5.1933 (Austrian National Library, ANNO), Clemens Krauss, News Chronicle, 5.5.1934 (British Library)

Pisk repeatedly received praise for the costumes she designed for various theatre projects. For example, when, at the beginning of 1933, the artists’ association “Hagenbund” showed a representative graphics exhibition on the theme of “The Dance”. Gertrud Bodenwieser also appeared at one of the dance performances accompanying the exhibition, and the costumes that Lizzi Pisk had designed for her were particularly praised.[46] And at the end of that year, it was the “splendid costumes” that she had contributed together with Herbert Ploberger for the revue “Alles nach Maß” by the popular cabaret artist Karl Farkas, which were singled out for special praise by the critics.[47]

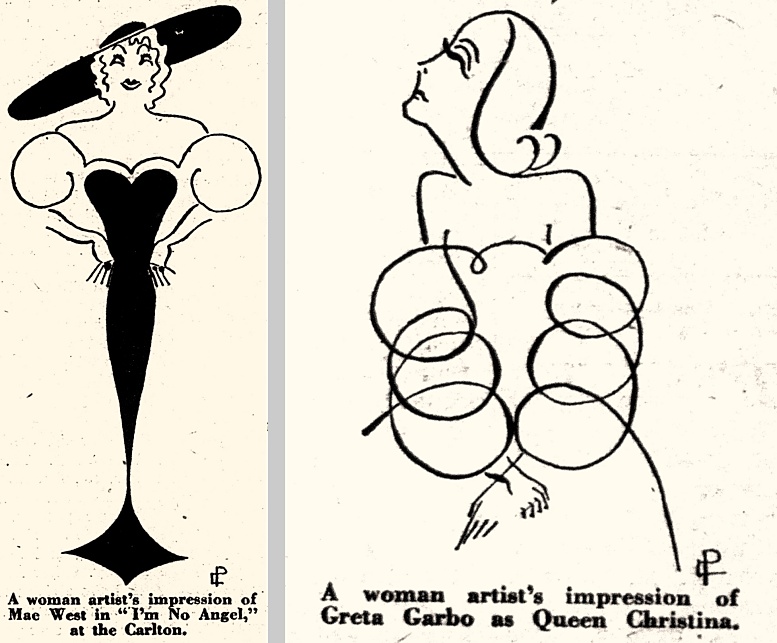

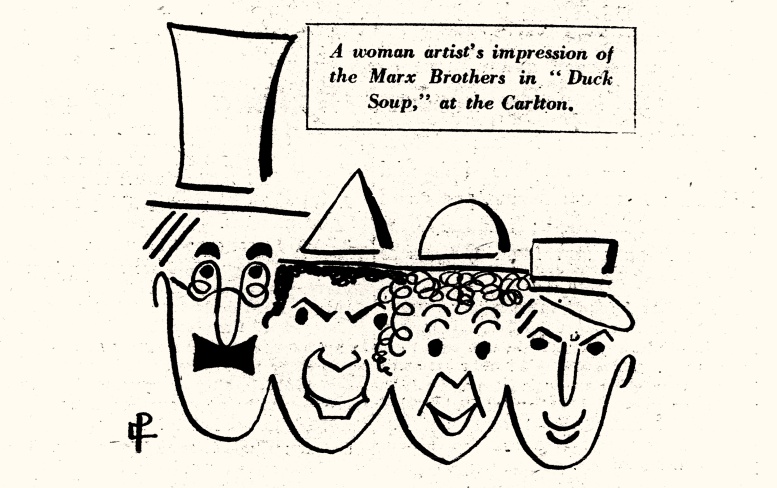

1933 was the year in which Pisk first came to England, which she subsequently visited regularly. Here it was initially her graphic talent that gave her a brilliant start: from February to April 1934, more than twenty of her caricatures, mainly of film stars, appeared in the daily newspaper “Evening Standard”.[48] The spectrum ranged from Mae West to Greta Garbo and the Marx Brothers. In May 1934, she joined the “News Chronicle” as a cartoonist, for which, however, she only produced a few works.[49] In addition, illustrations drawn by her could also be found in the traditional British magazine “Tatler”.[50]

Caricatures in the “Evening Standard”: Mae West, 5.2.1934; Greta Garbo, 19.2.1934 (both: British Library)

Due to her international commitments, Pisk was unable to continue her pedagogical work in Vienna. At the beginning of 1934, it was announced in the “Verordnungsblatt des Stadtschulrates für Wien” (Bulletin of the Municipal School Board of Vienna) that the “Private School for Gymnastics and Artistic Dance, and for Ornamental and Figural Drawing” was “currently not being run”.[51] Nevertheless, she continued to be listed in the Vienna address book “Lehmann” as a “gymnastics teacher” until 1936, then in 1937 and 1938 she appears there with the occupational title graphic artist.[52]

Marx Brothers, Evening Standard, 26.2.1934 (British Library)

In addition to graphics, costume designs continued to be an essential part of Pisk’s work. On the occasion of a performance by the “Gertrud Bodenwieser Dance Group” in the Great Music Hall in Klagenfurt on 11 January 1934, for example, the review stated: “The effectively conceived costume design by Lizzi Pisk, with its characteristic drawing and colour effect, once again contributed significantly to the beautiful impression of the performances […].“[53] And in July 1934, on the occasion of an open-air performance by Bodenwieser in Vienna’s Burggarten, the “Neues Wiener Journal” wrote: “Costume designer Lizzi Pisk deserves special praise for the tasteful and effective dance dresses”.[54]

Pisk apparently travelled back and forth between England and Austria in those years. In the fall of 1934, she was involved in an impressive large-scale project in London as a costume designer. From 15 to 20 October, seven performances of a historical festival on the history of the British Labour Movement took place at the Crystal Palace in London. The series of events, organised by the “Central Women’s Organisation Committee of the London Trades Council”, combined music, dance and drama. 1200 performers and 200 dancers were involved. The script was by Matthew Anderson, the music by Alan Bush. And Lizzi Pisk was responsible for the design of the costumes in cooperation with the “LCC Central School of Arts and Crafts”.[55]

In 1937, due to the increasingly repressive conditions, especially in Germany but also in Austria, Pisk decided to move permanently to England.[56] In 1947, she took on British citizenship.[57] Soon interesting work assignments had opened up for her in London as well, as one can read in a short biography authorised by her: “Here, too, she was engaged in stage and costume designs, choreography, taught at theatre and art schools, but also exhibited drawings.”[58]

A particularly warm welcome was given to Pisk by the critic H. K. Thomas in the prestigious “Penrose Annual”. He dedicated a separate article to her, which began with the words: “Lizzi Pisk comes from Vienna, and her work has all the liveliness and impudent gaiety typical of that carefree city. She has long been a famous figure in Vienna, and her caricatures, that appeared regularly in the morning paper after every important first night or sporting event, were a breakfast-time treat for all intellectual Vienna.

Her art is pre-eminently the kind that conceals art, and her best effects are achieved by an economy of line: by what she leaves out rather than what she puts in.”[59] Even if the author probably had an overly optimistic view of the cheerful life of Vienna in those years, the analysis of Pisk’s drawing art was definitely accurate.

Not only did Pisk achieve remarkable recognition as a graphic artist in London, she also very soon received a teaching position at the famous “Royal Academy of Dramatic Art” as a “teacher of Mime”.[60] In her further teaching activities, she succeeded in reconciling her two main talents, that for the visual arts and that for theatre. She once summarised her numerous activities in Great Britain as follows: „Combined visual expressions in drawing, design, and choreographical work; exhibited pen- and brush-drawings in the Redfern Gallery[61], designed Stage-sets, choreographed for the Royal Shakespeare Company, the Old Vic Theatre, the National Theatre, the Royal Exchange Company (Manchester), and for T.V. and Film-productions, taught at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, the Old Vic School (London), the Bath Academy of Art, and the Central School of Speech and Drama.”[62]

A highlight of her choreographic work was certainly her cooperation with Vanessa Redgrave for the film “Isadora”, in which the famous actress played the dancer Isadora Duncan under the direction of Karel Reisz (1968).

Book cover using a photograph of Litz Pisk together with Vanessa Redgrave at the rehearsals for the film “Isadora”

From the summer of 1970, Litz Pisk lived – as she herself put it – “semi-retired” in a cottage in the small town of Hayle in Cornwall and gave “drawing” as her main occupation.[63] However, she continued to work for the theatre on a case-by-case basis. For example, she was engaged for some productions of “Company 69” at Manchester University Theatre.[64]

In the rural tranquillity of Cornwall, she also took the time to summarise the principles of her teaching in the book “The Actor and his Body”. In his foreword to the work, first published in 1975, the British director Michael Elliot wrote: “Before she came to England she was a designer as well. Her distinguished past abroad and her work with the Old Vic School, and latterly the Central School of Speech and Drama, are in many ways even more important as an influence on the theatre than the productions in which she was directly involved. She is a great teacher and has changed many who will change the theatre.”[65] The book has become a bestseller and is currently in its fourth edition.

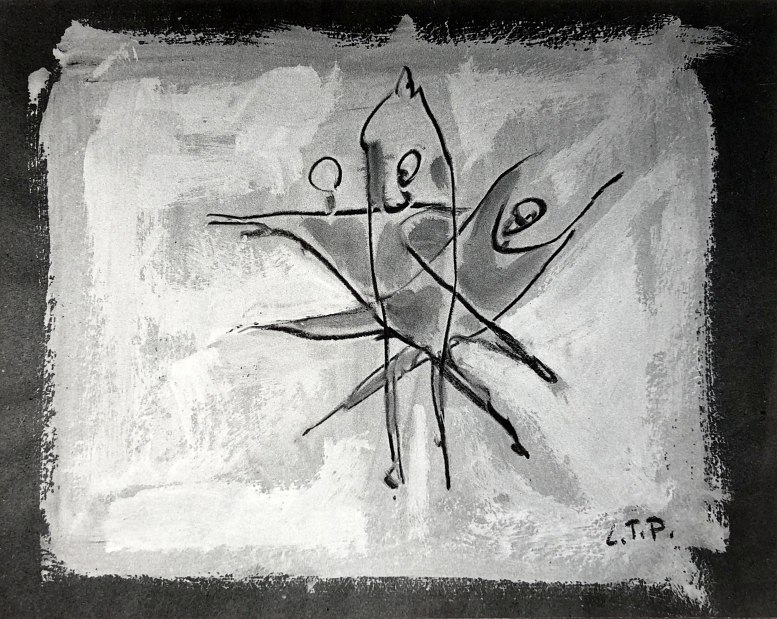

Litz T. Pisk, Moving Figure, 1982, promotional postcard for the exhibition at the New Art Centre in London

In the last decades of her life, Pisk returned with great commitment to her artistic beginnings, namely to drawing. In 1980 and 1982, she had solo exhibitions at the “New Arts Centre” in London’s Sloane Street[66] and in 1986 a presentation at the “Newlyn Art Gallery” in Penzance.[67] In December 1983, she wrote to Hans Weigel that after five weeks working on a theatre production in Manchester, which her friend Michael Elliot had persuaded her to do, she had now returned to her home and was glad to be “back at my drawing table.”[68]

On 6 January 1997, Litz Pisk died in St Ives in Cornwall. In his obituary in the British newspaper “Independent”, Pisk’s former student and later colleague George Hall stated: “None who worked with the movement teacher Litz Pisk, either as actor or student, will ever forget the sheer theatrical impact of her own movement, at once dynamic and sculptural, intense and totally possessed.”[69]

“Litz Pisk Studio” at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama (Photo: B. Denscher)

In 2019, a studio at London’s Royal Central School of Speech and Drama was named after Litz Pisk – in memory of her outstanding achievements as a teacher at this institute. Pisk’s merits in the field of dance and theatre have been and continue to be honoured accordingly – at least in Great Britain. Now, however, she has also to be rediscovered as an outstanding and independent graphic artist.

25.3.2023. German version first published on 11.2.2023.

[1] Born, Wolfgang: Kunstausstellungen und Vorträge. Lizzi Pisk im graphischen Kabinett der Buchhandlung Perles, in: Neues Wiener Journal, 28.10.1932, p. 7.

[2] Kind information from DSA Irma Wulz, BA of the Jewish Community.

[3] Litz Pisk, Letter, 17.11.1966 (Hans Weigel Estate, Wienbibliothek).

[4] Höfler, Ida Olga: Die Jüdischen Gemeinden im Weinviertel und ihre rituellen Einrichtungen 1848–1938/45: Der Politische Bezirk Gänserndorf. 1: Rituelle Einrichtungen, Begräbnisstätten, Strasshof 2015, p. 850f.

[5] Neuigkeits-Welt-Blatt, 27.6.1926, p. 18.

[6] University of Applied Arts Vienna, Online Student Database.

[7] Werkner, Patrick: Viennese Kineticism – a Futurismo Viennese? In: Viennese Kineticism. Modernism in Motion, Vienna 2011, p. 65.

[8] Minutes of the professors‘ meeting of 16.1.1924, quoted from: Vogelsberger, Vera: Sequenzen aus Kunsterziehung und Geisteswissenschaften, in: Kunst: Anspruch und Gegenstand. Von der Kunstgewerbeschule zur Hochschule für angewandte Kunst in Wien 1918–1991, Wien 1991, p. 287.

[9] Footnote 7.

[10] Litz Pisk Movement Notes, (Royal Central School of Speech and Drama [=RCSSD], Archive), quoted from: Tashkiran, Ayse: Introduction, in: Pisk, Litz: The Actor and his Body, London 2018, p. VIII.

[11] Footnote 7.

[12] Litz Pisk, Biographical Note, RCSSD, Archive.

[13] Kind information from Christina Kramer from the archive of the Max Reinhardt Seminar.

[14] Die Bühne, 18.11.1926, p. 3.

[15] Das interessante Blatt, 17.11.1927, p. 21.

[16] That Pisk was a student of Isodora Duncan’s sister Elizabeth, as is repeatedly claimed in the literature, cannot be verified on the basis of the current state of the sources. Nor is there any indication of this in a curriculum vitae written by Pisk (see footnote 14). In a letter to Patsy Child, Hilde Holger made a point of stating that Pisk had been her student: „There was never a Duncan-School in Vienna and if Litz would have gone to Elizabeth Duncan to Salzburg, she would have mentioned [it] to me. She was aged 19 years when she studied with me and I think I have the right to say that I was her teacher.“ (Letter from Hilde Holger to Patsy Child, 16.11.1997, RCSSD, Archive).

[17] Der Tag, 13.9.1928, p. 6.

[18] Das Kleine Blatt, 17.5.1929, p. 12.

[19] Die Stunde, 29.9.1929, S. 7.

[20] Verordnungsblatt des Stadtschulrates für Wien, 1.12.1929, p. 218.

[21] Der Wiener Tag, 1.5.1929, p. 8.

[22] Der Morgen, 3.2.1930, p. 4.

[23] Reichspost, 30.3.1930, p. 30; Neues Wiener Journal, 19.3.1931, p. 11.

[24] Der Tanz. Monatsschrift für Tanzkultur, 1930/8.

[25] Die Bühne, 1931/9(1), p. 8.

[26] It is sometimes erroneously claimed in the literature that Pisk created the stage design for the premiere of this opera in Vienna in 1932. However, as is well known, the premiere of the play had already taken place in Leipzig in 1930, and it was without Pisk’s participation.

[27] Straub, Wolfgang: Die Netzwerke des Hans Weigel, Wien 2016, p. 38.

[28] Weigel, Hans: In die weite Welt hinein. Erinnerungen eines kritischen Patrioten. Ed. Elke Vujica, St. Pölten 2008, p. 141f.

[29] Neues Wiener Journal, 27.4.1932, p. 11.

[30] Das interessante Blatt, 5.5.1932, p. 20.

[31] Reichspost, 7.6.1932, p. 9.

[32] Archives internationales de la danse, 1932/0, p. 4.

[33] Ibid, p. 8; Copies of some of Lizzi Pisk’s early costume designs are preserved in the estate of Gertrud Bodenwieser at the National Library of Australia. (Papers of Gertrud Bodenwieser, 1919-2020, Class MS 9263, Series 3. Costume designs, Item 2).

[34] Till, Charlotte: Oesterreich siegt im Pariser Tanzwettbewerb, in: Neues Wiener Journal, 9.7.1932, p. 5; Der Wiener Tag, 14.7.1932, p. 9.

[35] Malet, Marian: Litz Pisk, Dance and Theatre, in: Brinson, Charmian – Richard Dove (Ed.): German-Speaking Exiles in the Performing Arts in Britain after 1933, Amsterdam 2013, p. 93; Tashkiran, Ayse, (Footnote 11) p. VIII.

[36] Pisk, Lizzi: Tanzolympiade in Paris, in: Die Bühne, 1932/8(1), p. 34.

[37] Archives internationales de la danse, 13.1.1933, p. 32.

[38] Hall, Murray G.: Julius Klinger and Verlagsbuchhandlung Moritz Perles in Vienna, in: Denscher, Bernhard (Ed.): Viennese Posters. Art, Artists, Artwork. 1868–1938, Wolkersdorf 2022, p. 105ff.

[39] Lizzi Pisk, Letter to Moritz Perles, 5.9.1932 (Archive of the author).

[40] Maryška, Christian: Kunst der Reklame. Der Bund Österreichischer Gebrauchsgraphiker von den Anfängen bis zur Wiedergründung 1926–1946, Salzburg 2005 (=Design in Österreich, 1. Bd), p. 139; Copy of the membership card (No. 119) of the „Bund Österreichischer Gebrauchsgraphiker“, Archive of the Austrian Theatre Museum.

[41] Der Wiener Tag, 22.11.1932, p. 7.

[42] Die Stunde, 23.10.1932, p. 5.

[43] Starting with: Die Bühne 1931/9(1), p. 8.

[44] Starting with: Der Wiener Tag, 3.9.1932, p. 8.

[45] Moderne Welt 1932/10: Conductor Robert Heger (p. 11), actor Hans Moser (p. 16) and actress Frieda Richard (p. 17).

[46] Der Wiener Tag, 23.2.1933, p. 8.

[47] Neues Wiener Journal, 29.12.1933, p. 9.

[48] Starting with: Evening Standard, 5.2.1934, p. 8.

[49] Starting with: News Chronicle, 5.5.1934, p.11.

[50] Litz Pisk, Personal curriculum vitae (RCSSD, Archive).

[51] Verordnungsblatt des Stadtschulrates für Wien, 1.2.1934, p. 9.

[52] Wiener Adreßbuch, Lehmanns Wohnungsanzeiger https://www.digital.wienbibliothek.at/wbrobv/periodical/titleinfo/2316398

[53] Freie Stimmen, 13. 1. 1934, p. 3.

[54] Neues Wiener Journal, 14. 7. 1934, p. 11.

[55] The Redress of the Past. Historical Pageants in Britain https://historicalpageants.ac.uk/pageants/1152/

[56] According to the registration records in the Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna, Pisk deregistered from her address Wien 20, Wasnergasse 31/12 in November 1937.

[57] The London Gazette, 24.6.1947, p. 2878.

[58] Baum, Elfriede: Litz Pisk, in: Die uns verließen. Österreichische Maler und Bildhauer der Emigration und Verfolgung, Wien 1980, p. 166; Litz Pisk, Biographical Note (RCSSD, Archive).

[59] Thomas, H. K.: Lizzi Pisk, in: The Penrose Annual. A review of the Graphic Arts, 1937, p. 76f.

[60] Certificate „To Whom It May Concern“ from the Director Kenneth R. Barnes, October 1939 (RCSSD, Archive).

[61] Ceri Richards, Paul Gauguin, Litz Pisk. Redfern Gallery, London, September 28th to October 21st 1944 [Catalogue].

[62] Litz Pisk, Biographical Note (RCSSD, Archive).

[63] Baum (Footnote 61).

[64] Litz Pisk, Letter to Hans Weigel, 10.8.1970 (Hans Weigel Estate, Wienbibliothek).

[65] Elliot, Michael: Introduction, in: Pisk, Litz: The Actor and his Body. Introduction by Ayse Tashkiran. 4th Edition, London 2018., p. XXXIII.

[66] Invitation cards (Hans Weigel Estate, Wienbibliothek).

[67] Litz Pisk. Drawings 1942–1985, [Exhibition brochure] Penzance 1986.

[68] Litz Pisk, Brief an Hans Weigel, 30.12.1983 (Hans Weigel Estate, Wienbibliothek).

[69] Hall, George: Obituary: Litz Pisk, in: Independent, 29.3.1997, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-litz-pisk-1275650.html