At the end of 1910, the “1. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstlerinnen Österreichs” (1st Exhibition of the Austrian Association of Women Artists) in the Vienna Secession was a confident statement by female artists, with 300 artworks on show.[1] From the early Renaissance through to the present day of the age, a broad spectrum of styles was displayed. Newspaper reviews described the exhibition as an extraordinary event, with responses ranging from genuine enthusiasm to ignorant condescension and cynical malice. “The art created by women does them credit!”, one reviewer wrote with an impassioned cry[2], while another also included mention of an “emasculated Secession”[3]. Publisher Arthur Roessler – who was a known supporter of Egon Schiele – even went as far as to make claims in the social democrat newspaper “Arbeiter-Zeitung” that demonstrate the widespread prevalence of antifeminist trends in Austria at the time, regardless of political faction. For instance, he declared: “In her very nature, the woman is inexpert, reproductive, and – as she is so tremendously important as a stimulator – she should not have to struggle with problematic activities that allow her to produce a mediocre achievement at best compared with that of a man.”[4]

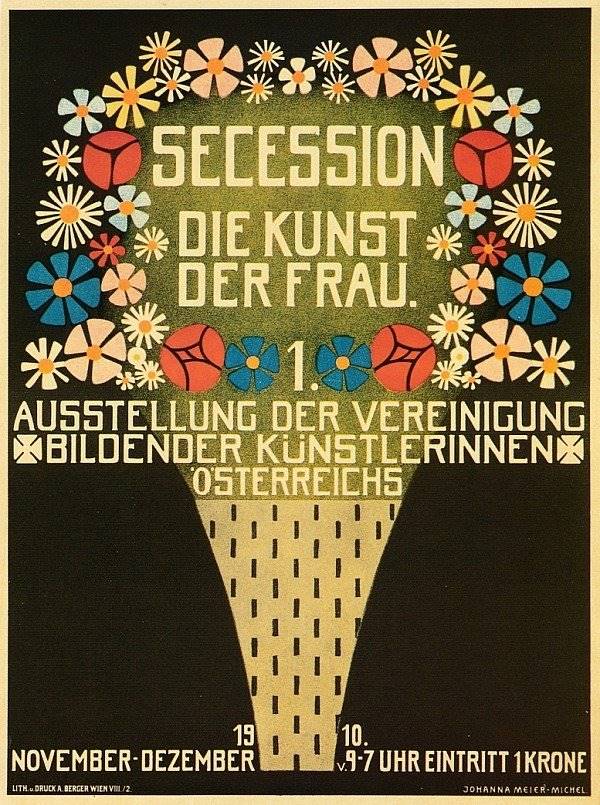

However, this exhibition of works by artists such as Angelika Kauffmann, Marie Bashkirtseff, Hermine Heller-Ostersetzer, Olga Wisinger-Florian, Tina Blau and Käthe Kollwitz serves as evidence that these creations were significantly better than just a “mediocre achievement compared with a man”. The exhibition poster alone, as the first of its kind to be designed by a woman for the Vienna Secession, displayed remarkable quality. At the end of her detailed review of the exhibition in the magazine “Neues Frauenleben”, writer Leopoldine Kulka takes a critical look at the poster: “Upon leaving the exhibition, once more we caught sight of the poster with its colourful flowers (by Johanna Meier-Michel, who used the same motif for a small sculpture in the exhibition with a truly attractive effect), whose graceful tastefulness sets itself apart from contemporary posters that are frequently so enigmatic and the unmodern ones that are so boring. May outward grace and inward solemnity be the characteristics out of which women’s art will grow.”[5]

Johanna Meier-Michel occupied a special role both as an exhibitor and also the designer of the exhibition poster, as mentioned above. Her biography is symptomatic of a woman who chose to make a living out of art in the late 19th century by carving out her own path.

There is an astonishing lack of literature on the life and works of this artist, despite the fact that her creations have experienced enduring success and are still popular, and although her small sculptures are sold by art traders even today. Neither of the two German-language biographical art lexica – “Thieme-Becker” and “Vollmer” – includes an entry for Johanna Meier-Michel. She is only mentioned briefly in the section on her husband Emil Meier in “Thieme-Becker”: along with numerous other cases where female artists married to another artist are only perceived in connection with their husbands, this is a striking indication of the long-prevailing disregard for independent artistic achievements by women.

Johanna Michel was born on 21 June 1876 in Česká Lípa.[6] She attended art school in Vienna, initially in the newly established “Kunstschule für Frauen und Mädchen” (Art School for Women and Girls) from 1897, where she studied with the renowned sculptor Richard Kauffungen[7]. From 1901 to 1905 she studied metal sculpture with Stephan Schwartz and in the specialist enamel atelier with Adele von Stark at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Arts and Crafts). Further experience as an artist was gained during periods in Munich, Paris and Italy. In 1905 she married the sculptor Emil Meier, who also came from North Bohemia. The couple worked together on many occasions.

Besides the poster for the art exhibition, there is no knowledge of any other works of graphic design by Meier-Michel. A lack of suitable opportunities prevented her from creating further works with the talent shown in this affiche. However, this one single poster occupies a very special status owing to its aesthetic quality and its cultural significance for the development of women’s art in Austria, and Meier-Michel has therefore earned the right to be perceived as a graphic designer. Specialising in reliefs and small sculptures, she worked first and foremost for the “Wiener Kunstkeramische Werkstätte” (Vienna Art Ceramic Workshop). She therefore played an active role in exhibitions by the “Vereinigung bildender Künstlerinnen Österreichs”, and received many positive reviews from art critics.

Although Johanna Meier-Michel lived and worked in Vienna with her husband, she maintained contact with her home in North Bohemia. She created a bronze bust of textile entrepreneur Heinrich Wedrich for her birthplace, for example – Wedrich had bequeathed his art collection to the city of Bohemian-Leipa upon his death in 1906. This was followed by portrait reliefs for the monument erected in 1907 for the German-Bohemian writer Anton Amand Paudler and the memorial fountain completed in 1924 in honour of composer Franz Mohaupt. The metalwork here was removed by German occupying forces during World War II and melted down for use in the war. After their home in Vienna suffered bomb damage, Meier-Michel and her husband moved to Česká Lípa in 1944[8], where she died in April 1945.[9] In relevant literature, in the catalogues of public collections[10] and also by art traders, her year of death is either omitted or usually incorrectly specified as 1930, in one instance it is even given as 1972.

This text is part of the article: Bernhard Denscher, Women in early graphic design: Three perspectives, in: Denscher, Bernhard (Ed.):Viennese Posters. Art, Artists, Artwork. 1868–1938, Wolkersdorf 2022, p. 49ff.

Translation: Rosemary Bridger-Lippe

Update 14.6.2023: Johanna Meier-Michel died on 1 April 1945, see: Johanna Meier-Michel und Česká Lípa

[1] Die Kunst der Frau, Ausstellungskatalog der Vereinigung Bildender Künstler Österreichs (The Art of Woman, Exhibition catalogue of the Austrian Association of Women Artists), Wien 1910.

[2] Das Vaterland, 17 November 1910, p. 2.

[3] Wiener Sonn- und Montagszeitung, 14 November 1910, p. 1.

[4] R[oessle]r, A[rtur]: Die Kunst der Frau. In: Arbeiter-Zeitung, 26 November 1910, p. 3.

[5] Kulka, Leopoldine: Die Kunst der Frau. In: Neues Frauenleben, 1910/12, p. 355.

[6] There is no monograph on Meier-Michel. Since the mid-1990s her name has appeared repeatedly in publications on gender-sensitive art history. For example: Plakolm-Forsthuber, Sabine: Künstlerinnen in Österreich 1898–1938: Malerei-Plastik-Architektur, Wien 1994, pp. 65, 68, 93; Johnson, Julie M.: The Memory Factory. The Forgotten Women Artists of Vienna 1900, West Lafayette 2012, pp. 272, 290, 386. The admirable work published in several volumes by Ilse Korotin entitled “biografiA. Lexikon österreichischer Frauen” (Encyclopaedia of Austrian Women) includes an entry written by Megan Brandow-Faller (Wien 2016, Vol. 2, p. 2214f.). Meier-Michel is also mentioned in the recently published book “Women Artists of the Wiener Werkstätte”, eds. Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Anne-Katrin Rossberg and Elisabeth Schmuttermeier (Basel 2020).

[7] Stieglitz, Olga – Gerhard Zeilinger: Der Bildhauer Richard Kauffungen (1854–1942). Zwischen Ringstraße, Künstlerhaus und Frauenkunstschule, Frankfurt am Main 2008, p. 179.

[8] Kindly supplied by historian Ladislav Smejkal from Česká Lípa in an email dated 2 July 2018.

[9] Karpf, Josef: Wekelsdorf. Markt Wekelsdorf mit Buchwaldsdorf, Neuhof und Stegreifen. Ober-Wekelsdorf. Unter-Wekelsdorf, Forchheim 2003, p. 223f.; this date is also found in the registration records section of the Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv (Vienna City and State Archives) (information received in writing dated 26 June 2018): Emil Meier and his wife registered in Vienna’s 3rd district, Seidlgasse 14/21, on 21 October 1929, although no notice of departure has been found. On 9 May 1946 Emil Meier returned to Vienna’s 3rd district, registering at the address Landstrasser Hauptstraße 11/4 (marital status: widowed). “Lehmann’s Adreßbuch” from the year 1942 contains the following details of the couple: “Meier Emil (Johanna) Bildhauer u. Emailleur, Atelier, III, Seidlg. 40”.

[10] One positive exception in this regard is the “Österreichische Galerie Belvedere”, which lists the date of death in its artist database as 1945 owing to archive content for Rudolf Schmidt and Werner Schweiger.