A painting comes to life before your very eyes – the characters climb out and start talking to one another. We are used to scenes like this in movies, plays and stories, but the people depicted on posters can develop a life of their own as well, and they can even fall in love with each other. The writers Leo Einöhrl and Josef Koller used this idea to create a “Phantastisches Singspiel” that was performed with great success at Vienna’s Ronacher theatre in 1911, with music by Ernst Wolf. The libretto was presented to the “hochlöbliche K.K. Polizei-Direktion” (honourable imperial and royal police authorities) for approval, which it received without further ado, and is now found in the theatre censorship collection as part of the Lower Austrian Archives in St. Pölten.[1]

Title page of the textbook for the singspiel “Verliebte Plakate” (Posters in love), 1911, (Niederösterreichisches Landesarchiv)

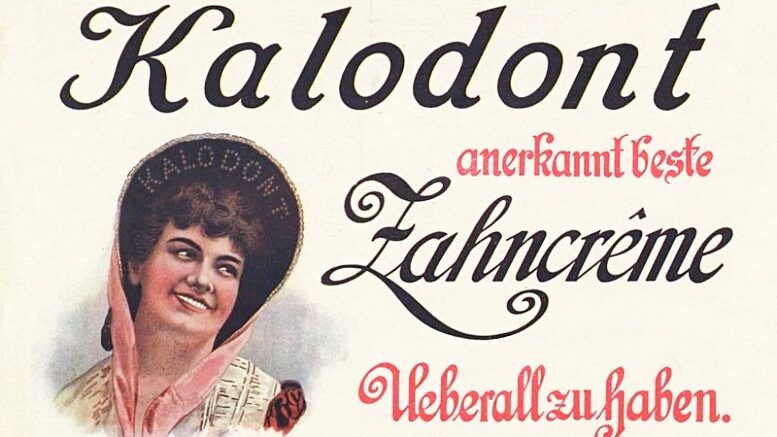

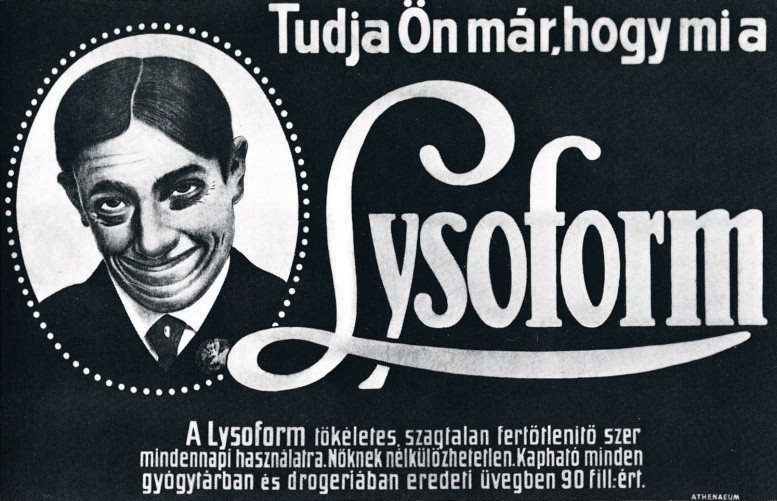

The main protagonists in this one-act work were taken from posters that were highly popular at the time: a young lady holding an outsized tube of Kalodont toothpaste in her arms, and a man advertising disinfectant by Lysoform with an impish grin. These two products were relatively new on the market, and were associated with a modern lifestyle, innovative research, and the era’s pursuit of hygiene in all areas of life. Kalodont, developed by Viennese company F.A. Sarg’s Sohn & Co, was the first toothpaste (or “tooth soap”, as it was initially called) in the world to be supplied in tubes when it was launched in 1887. In the beginning the product was advertised as “American”, with the word likely being used as a synonym for modern.

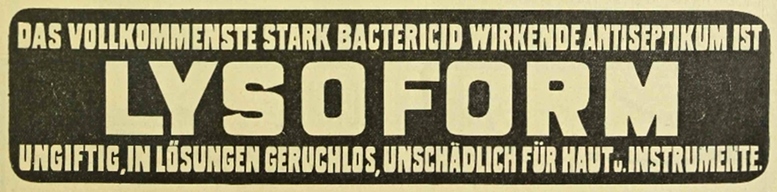

Lysoform, a formaldehyde soap solution for which the Berlin researchers Hans Rosemann and Alfred Stephan applied for a patent in 1900, was initially used predominantly in medicine and cosmetics but developed very rapidly into a widespread domestic product.

From the outset, the promotion of both products included an extensive use of newspaper advertisements, promotional cards, poster stamps and posters – and even though several other motifs were soon used in each case, for a long time it was both the Kalodont lady and the Lysoform man who were the signature images for their respective product.

The Kalodont lady first appeared on the marketing stage for Sarg’s toothpaste in the 1890s.[2] But even back in the 1880s she is found on the “Actors and Actresses” series of cigarette cards that were widespread in the US at the time. Sized roughly 3.5 x 7 cm, these cards were used to stiffen cigarette packets and were popular collector’s items. The “Actors and Actresses” series consisted of several hundred portraits, although they were almost exclusively actresses. Each portrait was named – as was the Kalodont lady, Elsie Gerome.[3] This was a stage name, however, as her name was actually Fannie D. Hills – she performed in the 1880s and 1890s on stages in New York, Connecticut and Indiana, and died on 18 February 1912 in Bridgeport/Connecticut.[4] Her portrait from the “Actors and Actresses” series is found on cigarette cards both for Cross-Cut Cigarettes by W. Duke, Sons & Co and also for Virginia Bright Cigarettes by Allen & Ginter.

Left: Advertisement, 1897 (ANNO – Österreichische Nationalbibliothek) / Right: Poster, ca. 1905 (Albertina Wien)

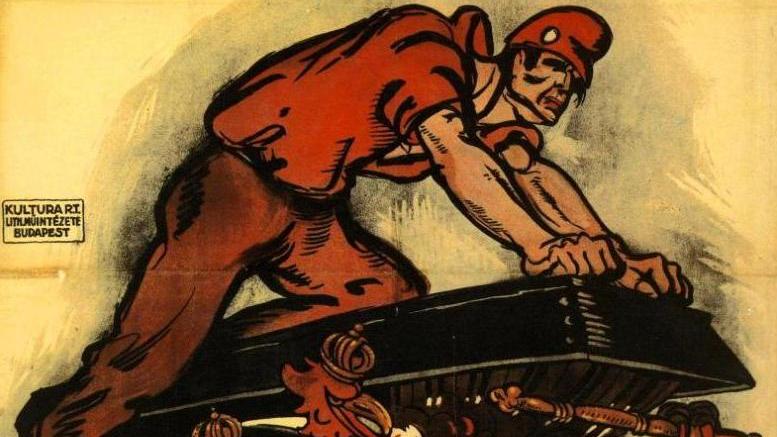

The person chosen as the Lysoform advertising figurehead was Hungarian actor Gyula Hegedűs (real name: Gyula Mihály Heckmann, 3 February 1870 – 21 September 1931), who was extremely popular in his home country, especially as a comedian. This particular choice was linked to the fact that Lysoform – which was sold in Austria/Hungary – was produced in Budapest, in the chemical plant Keleti & Murányi in the district of Újpest. However, Hegedűs is said to have also been chosen as the figurehead because one of the two company owners, Iván Murányi, was a big fan of the actor and apparently looked quite like him as well.[5] For a long time the posters routinely displayed just one question – often together with a large question mark: “Have you heard of Lysoform?” or in German: “Kennen Sie schon das Lysoform”, and in Hungarian: “Tudja Ön már, hogy mi a Lysoform?” In 1928, the “Hebammen-Zeitung” at the International Congress of Midwives in Vienna reported: “Here too, the Lysoform factory – the chemical plant in Ujpest – asked every visitor the same question: ‘Have you heard of Lysoform?’ and lo and behold, there wasn’t a single person who hadn’t already seen the friendly face smiling on that hugely successful Lysoform advertisement.”[6]

Left: Fannie D. Hills – Elsie Gerome, ca 1895 (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung) / Right: Gyula Hegedűs, 1930

Both the Kalodont lady and the Lysoform man were displayed on innumerable billboards when Leo Einöhrl, Josef Koller and Ernst Wolf produced their Singspiel “Verliebte Plakate” (Posters in love). The scenario described at the beginning of the script makes reference to the posters, and additionally reveals that the scenery and costumes were apparently quite modest:

“An evening setting on the street. In the background, across the entire width of the stage, a billboard is visible. Besides announcements for theatre performances and other advertisements, the familiar Kalodont and Lysoform posters are hanging next to one another. The head and a chest section have been cut out of the posters to allow space for the heads of the actor and actress. To enable them to get in and out of the posters easily, the lower part of the two posters has to be equipped with a two-piece swing door. This must be concealed by posters so the audience can only see the billboard when the curtain goes up. – Lanterns, trees and a garden bench in front. (Street similar to the Ring Boulevard).”

Besides the two protagonists, the billsticker appears as a supporting character (“white overcoat, a familiar type, pushing his car in front of him, in a daze”). He is the catalyst of the work’s short and relatively simple storyline because – as we learn from his monologue, in the form of a couplet – he has been told to paste over the Kalodont and Lysoform posters with new ones, as they have already been up for 30 days. But before he does this, he wants to go to a tavern to buy a glass of wine (“it could be two or three, though”). The two characters on the posters, startled by the announcement, come out of the billboard, confess their love for one another and intend to run off together, ideally to the United States (because, as the Lysoform man says: “Europe leaves me cold, / Since I don’t love what’s old!”). But then they spend too much time thinking (in many different songs) about whether their English skills are adequate or if they would feel more at home in Vienna. The billsticker returns, the two of them hurry back to their places, and are pasted over with the new posters.

Advertisement, 1905 (ANNO – Österreichische Nationalbibliothek)

First performed on 13 January 1911, the work was very well received by the audience – as reported in various newspapers. “Thanks to its energetic portrayal” by the soubrette Olga Barco-Frank and the popular operetta tenor Joseph Josephi, the “lively little piece”[7] was “given a very friendly reception”[8] and was included in the repertoire of the Ronacher theatre until February – longer than initially planned – as it caused “outpourings of merriment every evening”[9]. In the slightly more detailed article on the production in the “Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung”, there is a note referring to product placement, which was customary at the time:

“The idea behind this little work is likely to have appeared in the minds of its authors during one of the many operettas where champagne is drunk, to make the audience aware of certain brands of champagne on world-renowned stages. But here it is tackled with greater openness and wit; the advertising itself is the subject of the storyline”.[10]

It remains unclear which of the two authors had the idea. Both were very successful in the entertainment genre: born in Vienna on 3 July 1878, Leo Einöhrl wrote numerous Viennese songs. He was a journalist and newspaper publisher, and wrote – together with Josef Koller and with music by Ernst Wolf – the libretto for the operetta “Wiener Mädeln”. In September 1942 he was deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp and was murdered there on 14 April 1943. Josef Koller, born in Vienna on 18 August 1872, was successful as a folk singer, actor, and particularly a writer of comedies. He also gained recognition as a folksong researcher and for his work “Das Wiener Volkssängertum in alter und neuer Zeit”, published in 1931. In 1938 Koller emigrated to London, where he died on 15 October 1945. Ernst Wolf, who composed polkas and waltzes for the Singspiel “Verliebte Plakate”, “whose undemanding character gives them the advantage of being kind to the ear”[11], was born in Vienna on 24 August 1883 and initially worked as a bank clerk, then as a composer and pianist. Wolf died on 8 July 1932 in Purkersdorf, near Vienna.

The last verifiable production of “Verliebte Plakate” was performed in Vienna’s Rotgasse in March 1914, at the “Etablissement Adlon” which was managed by Josef Koller at the time. Above all, the audience’s favourite – Rudolf Kumpa – was “rapturously acclaimed”[12] in his role as the Lysoform man. After this, however, the “little operetta”[13] apparently faded into obscurity. But Kalodont and Lysoform remained on billboards for many more years, albeit with certain adaptations in some places. When World War I broke out, the Lysoform plant seized the opportunity to “adapt” its figurehead in line with the times – and so the grinning man was then (on a poster by Hungarian graphic designer Sándor Bortnyik) dressed in uniform.

Poster, Hungary, 1926

In April 1916 author Karl Kraus wrote in his journal “Die Fackel”: “The Lysoform face is the face of our era. It can be seen, smirking, on every poster. The remedy is one of those remedies – whose names always end with ‘-it’, ‘-in’, ‘-ol’ and ‘-form’ – that humankind has only needed since they were invented, and without which the problems would not exist that were the reason for their invention. But the face that recommends the product is the era itself. In this part of the world, where all events are louder and more colourful than elsewhere, you neither look nor listen when you walk past a board, only time stands still and smirks.”[14]

An analysis of simple examples of popular culture, as represented by the Singspiel “Verliebte Plakate”, shows that these are certainly not merely of interest from a media-historical perspective, but they can also be insightful documents on various facets of cultural history – such as the history of advertising.

Denscher, Barbara:“Verliebte Plakate” – Posters in love, in: Viennese Posters. Art, Artists, Artwork. 1868–1938. Aesculus Verlag, Wolkersdorf 2022, p. 75ff.

Translation: Rosemary Bridger-Lippe

[1] Einöhrl, Leo and Josef Koller: Verliebte Plakate. Phantastisches Singspiel. Music by Ernst Wolf. Vienna 1911. NÖ Landesarchiv, NÖ Reg. Präs Theater TB K 032/03.

[2] The earliest verifiable evidence for the use of this advertising motif includes advertisements published in numerous issues of the weekly magazine “Wiener Bilder” during the years 1897 and 1898.

[3] The October 1931 issue of “Wiener Magazin” also examined the identity of the Kalodont lady, and wrote that it is a “very beautiful American woman called Elise Gerome” (p. 38).

[4] Cf.: The Bridgeport evening farmer, 19.2.1912, p. 6.

[5] Cf.: S. Nagy, Anikó: Tudja ön már, hogy mi a lysoform? In: Acta Musei Militaris in Hungaria, A Hadtörténeti Múzeum Értesítöje 12, Budapest 2011. p. 148f.

[6] Hebammen-Zeitung, 1.5.1928, p. 103.

[7] Arbeiter-Zeitung, 15.1.1911, p. 6.

[8] Deutsches Volksblatt, 15.1.1911, p. 7.

[9] Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 6.2.1911, p. 10.

[10] Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung, 15.1.1911, p. 71.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Neues Wiener Journal, 22.3.1914, p. 37.

[13] Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 15.3.1914, p. 16.

[14] Die Fackel, Nos. 418–422, 8.4.1916, p. 10.