Innumerable posters have been designed for circuses, cabarets, magicians, actors, animal shows and human zoos. Looking back to the beginnings of posters, as early as in the 18th century it was the travelling folk who hung up notices to publicise their attractions. From the end of the 19th century until the 1930s, the printing company Adolph Friedländer in Hamburg had a determining influence on the style of these posters.[1] And in fact the posters have hardly changed even today. The touted sensation is presented in an inflated design that is preferably colourful, and the performance venue is often affixed using overstickers or add-ons. In contrast, an entirely different kind of poster design was created by Theo Matejko in 1919 for magician Erik Jan Hanussen.

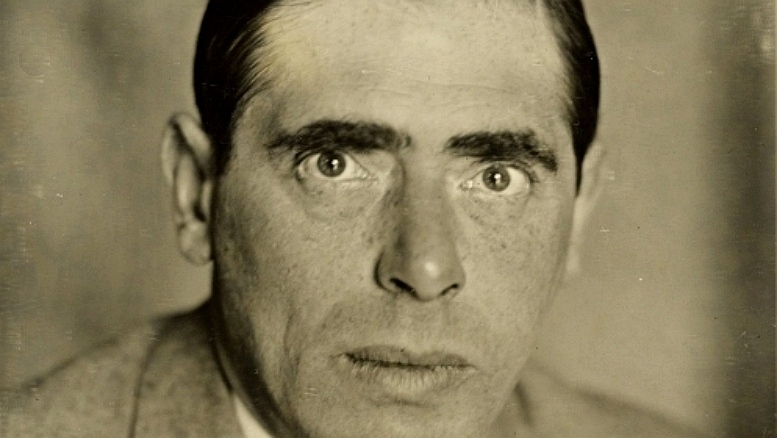

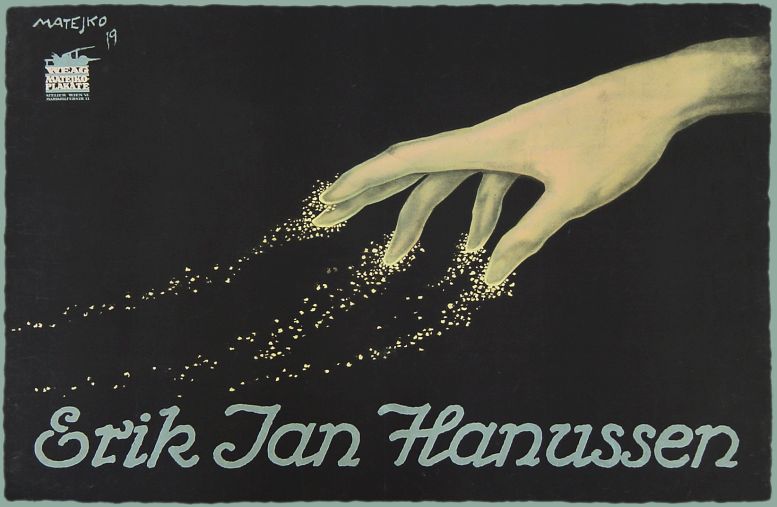

Theo Matejko (1893-1946), Erik Jan Hanussen, Vienna, 1919 (Deutsches Plakat Museum)

The poster

The main protagonist is a magician, who – contrary to usual practice – is not himself pictured. Entirely void of decoration and elaborate portrayals of spectacular tricks, even the colours are reduced to a minimum. Matejko chose a ‘counter-cliché’ to traditional posters, as it were. Only a single hand is shown, perfectly relaxed, and seemingly releasing a mystic energy into the room.

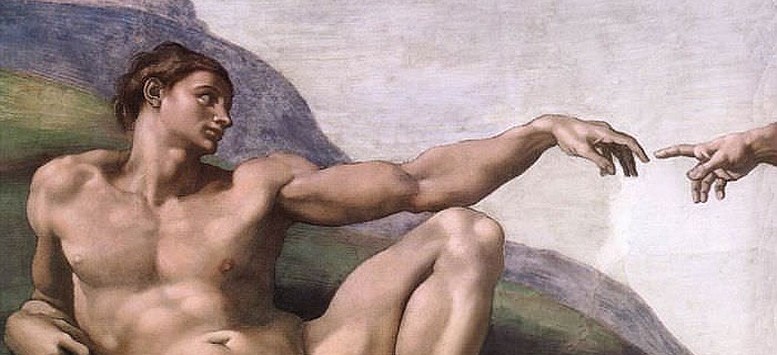

The poster dispenses with any kind of gimmicky effect. This removes all attempts to explain the mystic and unfathomable, appearing positively genuine in its message: this is somebody who simply has these powers that cannot be explained. There are no tricks, no false bottom involved. However, the initial assumption that this poster adopts an unpretentious approach takes a U-turn if, instead of accepting that the shape of the hand has originated from a random gesture, it is seen as having been borrowed from the hands in Michelangelo’s fresco “The Creation of Adam” in the Sistine Chapel.[2] Erik Jan Hanussen as the Enlightened or the Redeemer? Later on in life, Hanussen would display clear signs of megalomania and hubris.

Michelangelo Buonarotti (1475-1564), The Creation of Adam, 1512

As the poster contains no information on when and where Hanussen will be performing, why was it created in the first place? Research has unearthed several interesting facts about what Hanussen was doing round about at the time of its origin.[3] There were numerous appearances[4], his name often appeared in the tabloid press, and he also started film projects.[5] This means that Hanussen must have been “on everyone’s lips”. Nevertheless, the poster has not (yet) revealed any specific purpose. Three essential forms of interpretation can be derived from this: it is possible that details on the time and place of his performances were announced on a separate sheet – although this was no longer customary at the time. At best, stickers or overprinting are conceivable, familiar from blank posters, although no space was set aside for this on Matejko’s Hanussen poster. The second possibility is that it is a poster for inside use that was hung up at events by Hanussen himself to greet the members of his audience on an emotional level as they entered, and to arouse their curiosity before the performance. And the third possibility is that it is purely an image poster. This genre (although image posters were not known as such at that stage) had already emerged before 1914 with the development of “star posters” by designers such as Jo Steiner (1877–1935), although these posters used portraits of the protagonists as their focus.

And so Matjeko certainly created a special poster. Placing a person’s “abilities” centre-stage instead of showing their picture seems a new approach, even far-sighted. Nonetheless, there was apparently a lack of awareness that this could be a huge step in the development of advertising, as the idea was not adopted by a direct “successor”. In this context, the question arises as to why only one copy of the poster is known to exist. This is to be found in the German Poster Museum in Essen, which is part of the Museum Folkwang.

Hanussen was still in the early stages of his success when this poster was created. And its designer Theo Matejko was also at the beginning of his career. In 1927 he designed another poster for Hanussen, when they were both at the pinnacle of their professional lives. It is not known if Matejko and Hanussen were personally acquainted with one another.

The clairvoyant

Erik Jan Hanussen[6] was the pseudonym of German/Austrian clairvoyant Hermann Chajm Steinschneider, who was born in 1889 in the Vienna suburb of Ottakring. His career began in 1918 with sensational appearances. He ultimately became legendary as the “Magician from Berlin” – in the early thirties he fascinated audiences of up to 5,000 people at the Scala. From 1930 Hanussen announced the arrival of a supposed saviour, and he predicted Adolf Hitler’s political victory.

Hanussen was part of the NS scene long before the National Socialists seized power. Important NS personalities were among the handpicked guests in his “palace of occultism” in Berlin’s Lietzenburger Straße. On 26 February 1933 Hanussen invited them to join him for a very special séance, at which Graf Helldorf (head of the SA Berlin-Brandenburg) was also present. Here, Hanussen’s prophecies culminated in him declaring that he could see “flames coming from a big house” – and just one day later on 27 February 1933, this prophecy came true when the Reichstag burned. It was a prophecy that would ultimately cost him his life. But Hanussen was no clairvoyant. He received the necessary background information for his performances from numerous informants. Even the details of the impending fire at the Reichstag probably came from a reliable source, presumably Helldorf himself. On 24 March 1933 Hanussen was arrested and murdered by an SA commando on the orders of SA leader Karl Ernst. His body was found on 7 April 1933 by forestry workers in a fir plantation near Berlin and was later laid to rest at a cemetery in Stahnsdorf, near Berlin.

The extent to which Hanussen has occupied the minds of subsequent generations is evidenced in numerous films, for example. Probably the most remarkable of these is the film “Hanussen” from 1988, with István Szabó as director and Klaus Maria Brandauer in an impressive performance as Hanussen.

The designer

Theo Matejko[7] was born in Vienna on 18 June 1893 with the name Theo Matejka. He presumably received artistic training in Vienna. His extraordinary talent was discovered early on while doing military service during World War I. As a result of his accomplished illustrations for war reports, in 1917 he was transferred to the “art group of the war press bureau”. After the war Matejko worked as a press and poster illustrator. From 1919 he produced numerous posters, which immediately brought him huge success. Matejko initially worked with the Hungarian graphic designer Marcel Vértes (1895–1961) until they went their separate ways in 1920. Vértes settled in Paris, Matejko moved to Berlin where he quickly made a name for himself as a press illustrator for the “Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung”. His drawings also showed his passion for technology in general and autosport in particular. The publishers Ullstein-Verlag sent the talented illustrator on many journeys, such as to the USA on the Zeppelin, and enabled him to take part in automobile events. In the 20s and 30s Matejko designed numerous posters. From 1935 onwards he created drawings for “Die Wehrmacht”, illustrated reports on manoeuvres and then worked from 1939 onwards as a war report illustrator. Only minor works have survived from the post-war period. Matejko died on 9 September 1946 in Vorderthiersee after suffering a stroke.

Translation: Rosemary Bridger-Lippe

[1] In 1872 Adolph Friedländer (1851–1904) founded his lithography establishment in Hamburg-St. Pauli. The Friedländer style was shaped by artists such as Chr. Bettels, H. Schulz, L. Wildt and B. Rahjah. After around 1890 the posters received consecutive numbering. The last known numbered poster bears the number 9075 and is from the year 1935. Subsequent posters were no longer numbered and the Friedländer signet was no longer used. This anonymised approach was an attempt by Friedländer to protect them from the attention of the NS powers. This helped only until 1938, when the company was forced to close; the family emigrated to London. By this time, Friedländer had produced around 10,000 different posters.

[2] Michelangelo Buonarotti (1475–1564): The Creation of Adam, section of the ceiling fresco in the Sistine Chapel (1512). In the episode of the creation of humankind, the outstretching of fingers by God and Adam is the compositional focus, as this gives Adam the breath of life. God turns towards Adam, who is pictured like a resting athlete. His beauty seems to confirm the words of the Old Testament, according to which humankind was created in the image and likeness of God.

[3] I would like to thank Dr Bernhard Denscher for his research into Hanussen.

[4] Numerous performances were given in Vienna’s Apollo Theater, there was one appearance in the Großer Saal of the Vienna Musikverein and in January 1919 there were three performances in Prague. Mel Gordan mentions a series of appearances in the Apollo Theater that spanned four months and were attended by around 48,000 people (see fn 6, p. 71).

[5] Hanussen was offered five films by Kongreß Film, but only one film was eventually made: in 1919 “Hypnose” was produced with Otto Poll as director. Besides Hanussen, Borgia Horska and Grete Jacobson were in the leading roles. There were extensive press reports on the film, with both texts and pictures, including in the “Kinowoche”, Issues 1 and 5/1919, and in the “Neuer Kino-Rundschau”, Issue 127/1919.

[6] Literature on Jan Erik Hanussen (selection): Erik Jan Hanussen: Meine Lebenslinie, Berlin 1933; Kugel, Wilfried: Hanussen. Die wahre Geschichte des Hermann Steinschneider, Dusseldorf 1998; Gordan, Mel: Erik Jan Hanussen. Hitlers Jewish Clairvoyant, Los Angeles 2001.

[7] Literature on Theo Matejko (selection): Weber, Otto: Der Pressezeichner Theo Matejko 1893-1946. Das Buch zum 100. Geburtstag, Ober-Ramstadt 1993 (book accompanying the exhibition in Ober-Ramstadt Museum).