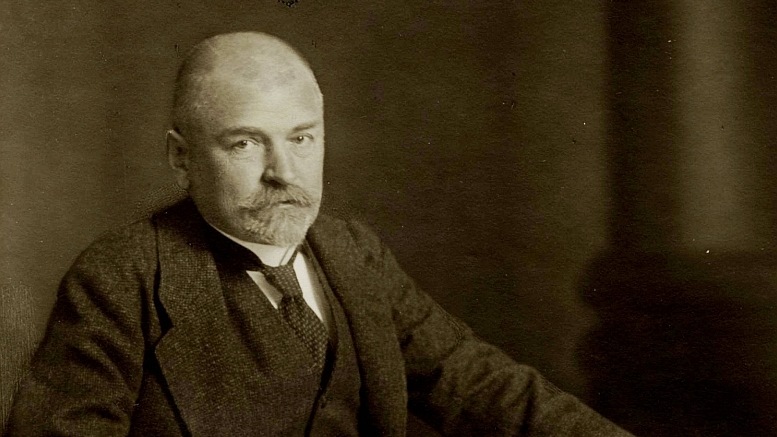

Ottokar Mascha was the first in Austria to deal with the subject of “Posters”, not only as a skilled collector, but also as a well-informed publicist.

Ottokar Mascha was born on 7th May 1852 in Pilsen in Bohemia (presently Plzen, Czech Republic)1 and worked initially in Prague2 and then, from 1897, in Vienna as a lawyer.3 In 1903 he married Sofie Effenberg.4

Over the years Mascha accumulated a considerable wealth, which allowed him to devote himself seriously to interests in the areas of collecting and bibliophilia. Here he paid particular attention as a collector to the work of the Belgian artist Félicien Rops as well as to both Austrian and international posters. His understanding of the need to combine his passion for collecting with great expertise was remarkable. By acquiring the Wolter collection in Vienna and the Griesebach collection in Berlin, he was able to bring together virtually the entire graphical work of Félicien Rops within his own possession.5

In their obituary for Mascha, the Österreichische Volkszeitung wrote with regard to his extensive poster collection: “It was not simply the biggest in Austria; it was one of the largest of any on the continent and exceeded all others with the number of unique copies it contained. Whatever incunabula it was possible to get hold of in this area, Mascha had it. He researched in police archives and within artists’ associations and, as a result, uncovered items which sooner or later would have been pulped. The Vienna police authorities lent sympathetic support, by making posters available which, at their time, had to accompany applications for public display as evidence of editorial control. On many occasions it was the only remaining copy which ended up in the folders of Dr. Mascha.”7

Ottokar Mascha was also anxious to embrace the contemporary artistic scene and to raise the qualitative level of Austrian commercial art – insofar as he had the opportunity to do so. In 1911 he therefore donated 400 posters from his collection to the Graphische Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt (Education and Research Institute for Graphic Art) in Vienna. The pieces were intended as visual material for teaching in order to enable improved performance in the area of applied art.8

However, despite his great dedication to the show, Mascha remained critical and distant in relation to the project’s implementation: The Vereinigung bildender Künstler (Union of Austrian Artists) essentially went to great lengths to provide no platform for unwelcome competition. It was noticeable, as a result, that apart from a few examples by Kolo Moser and Alfred Roller, the representatives of the Klimt group, who left the Secession in 1905, did not feature – even though their main focus actually was in the area of applied art in particular.

Ottokar Mascha reflects on this again in 1913, expressing his disappointment in the article Künstlerplakate und Plakatkünstler (Artists’ Posters and Poster Artists). “Never before has an instructive poster exhibition taken place in Vienna containing a selection of the best available international material of poster art incunabula covering the start right through to the present day.” In the same article, the author analysed the problems facing applied graphic art in Austria as follows: “The reason for the general lack of appreciation for the entire artistic genre is that public collections devote far less consideration to the acquisition, maintenance and accessibility of high quality and sufficient example material than is the case in other countries.”9

Ottokar Mascha was not only a collector of graphics, but was also actively in contact with the Wiener Bibliophilen-Gesellschaft (Bibliophile Society of Vienna) and with both Max von Portheim and Gustav Gugitz. When the Wiener Bibliophilen-Gesellschaft was founded in 1912, Mascha became a board member – assuming the role of “treasurer”, under the chairmanship of Hugo Thimig, head of the Hofburgtheater (Imperial Court Theatre) at the time.10

Ottokar Mascha was also well connected internationally; he was therefore in close contact with Hans Sachs – the distinguished German poster collector11 In the 1914 membership list of the Verein der Plakatfreunde (Friends of the Poster Society) Mascha ist listed as number 307, which, if he did not took his number from an earlier member, would correspond to the year 1911. Mascha published repeatedly in Das Plakat, the specialist magazine published by Sachs in Berlin, and reference is made here to his work in Vienna on a regular basis. Between 1912 and 1917 Das Plakat published six of his articles;12 he was mentioned no fewer than seventeen times from 1914 to 1918 for eminently important publications relating to the German language graphic art scene.13 In 1912, Das Plakat contained the following text: “Seeking to buy old Austrian posters, Ottokar Mascha”.14

In 1915, Hans Sachs himself wrote in a detailed and illustrated review of his Viennese colleague’s newly published work in Das Plakat.17

In 1917, an article followed by him on the subject of Die Plakatsammlung Mascha (The Mascha Poster Collection).18

It was in this year, 1917, that Ottokar Mascha donated the bulk of this poster collection to the Kupferstichsammlung (Engraving Collection) of the Imperial Court Library of the time, “with the intention that this collection, which is associated with my name, might bring glory to the fatherland and benefit posterity.”19 In doing so, he created the stimulus and the basis for the Austrian National Library’s outstanding poster collection.

The main element of his legacy, that is to say the valuable art posters, found their way after the war to the Albertina in the course of the transfer of the Kupferstichsammlung from the National Library and, here again formed the basis of the collection of applied graphic art in this prestigious institution.

Information varies as to the size of the collection. In 1970, Walter Koschatzky wrote on the subject: “The Mascha collection at the Albertina today comprises approximately 3,100 posters, of which around 1,360 originate from the area of the former Austro-Hungarian monarchy, 720 from Germany and 430 from France.”20 In 1995, Marianne Jobst-Rieder of the Austrian National Library defined this more precisely as “3,051 artists’ posters in 27 folders: According to a valuation by the company Artaria, the value of the Mascha Collection at the time amounted to at least 80,000 Austro-Hungarian Krone, it could well be higher, however, as it was hardly ever possible to bring together the collection in the form of a cohesive and instructive context.”21 By contrast, the current information from the Albertina reads: “Ottokar Mascha Collection (4,000 posters | Austria-Hungary, Germany, Western Europe, International | 1793 to ca.1918)”.22

In keeping with the zeitgeist, Ottokar Mascha further donated an extensive selection on the subject of “war art” to the National Library, which also contained 154 international posters, 830 war postcards, art and memorial prints, as well as caricatures on the subject of the Great War.23 Following 1918, only this collection of items remained in the National Library as it was. For this generous donation Dr. Mascha received the “Orden der Eisernen Krone 3. Klasse” (The Order of the Iron Crown, 3rd Class).

As a result of economic problems over the war and the post-war period, Mascha gradually felt it necessary to sell his remaining part of the collection on the art market. In 1914, elements of this collection appeared for sale at an auction by “Amsler & Ruthhardt” in Berlin.24 Between 14th and 16th May 1918 his collection of “modern graphic art” was sold in Frankfurt am Main at F.A.C.Prestel (in cooperation with “Amsler & Ruthardt” in Berlin), which, according to the text of the auction catalogue, comprised the following artists: “Greiner / Klinger / Meryon / Stauffer / Lautrec / Whistler, as well as Boehle, Gauguin, Goya, Haden, Leibl, Liebermann, Menzel, Munch, Redon, Thoma, Welti, Zorn and others.”25

His Rops collection comprising 1,055 paintings, watercolours, etchings and lithographs was auctioned in December 1921 as the “celebre Collection du Dr. Ottokar Mascha de Vienne” by the Galerie Georges Giroux in Brussels.26 Mascha by the Verein der Plakatfreunde in 1919 was listed as an active collector having a collection of 4000 posters and 3500 smaller ephemera, including especially war and War Loan posters and antique Japanese theatre posters.27

The Österreichische Volkszeitung wrote in their obituary for Mascha, that following the sales all he had left was the “extensive international poster collection comprising 3,225 pieces: With a heavy heart, Dr. Mascha took the decision also to sell these. Friends tried to generate interest in the city of Vienna; negotiations were conducted, but which made little headway. Then something unusual occurred. At the start of January in the previous year, a stranger drove up to the Mascha’s villa on Wambachergasse in Hietzing and made an offer to Dr. Mascha to buy the collection. The stranger made it clear that it had to happen on the spot – he had to leave immediately and could not say whether he would be able to return. The unknown person offered 10,000 Austrian Schilling and Mascha shook on the deal. He did not want to lose the chance of a sale, although the price was too low for him. The stranger paid the money immediately and left with the collection. It remains unknown as to who the buyer is, and where the irreplaceable and unique collection has ended up. The matter angered Dr. Mascha to such an extent that he suffered a heart attack. He was never able to recover from this.”

To what extent this seemingly mysterious account is due to the media demands of a popular daily newspaper of the 1920s, or whether the story actually occurred exactly as told is hard to judge today. That the story might be true is supported by the fact that the content of Mascha’s library was listed in detail in the probate proceedings, but nothing here refers to the existence of this poster collection.28 In addition to this, posters containing Mascha’s proprietary notes come up for sale in the art trade,29 and the large collection of the German Poster Museum has examples containing his seal.30

After the death of his wife Sofie on 2nd January 1926, Ottokar Mascha died as a result of his illness in Vienna in the Auersperg Sanatorium on 9th February 1929.31 On 12th February he was buried in Vienna’s Central Cemetery in group 122, row 15, number 4.32 Since then, Ottokar Mascha has been ever present in the relevant literature on posters right through to the internet age; by contrast extremely little has been known up to now about the life of the person who had such significance for Austrian cultural life.

Denscher, Bernhard: Ottokar Mascha, a Viennese Connoisseur, in: Le Coultre, Martijn F. (ed.): Hans Sachs and the Poster Revolution, Dutch Poster Museum, Hoorn 2013, p. 41-43 (Updated version).

| 1 | Vienna City and Regional Archive, Totenbeschau (post mortem inspection) J.A. 4206/1929. The author extends his thanks to Dr. Klaralinda Ma-Kircher and Dr. Karl Fischer from the archive for their kind and valuable assistance. |

| 2 | From 1891 to 1896 Mascha was registered as a lawyer at the ‘noble’ Prague address I, na Přikopě 15, according to “Leser, Vaclav: Adressar kralovskeho hlavino mesta Prahy, Praha 1891/1996”. |

| 3 | Koschatzky, Walter: Introduction in: Kossatz, Horst-Herbert: Ornamentale Plakatkunst. Wiener Jugendstil (Decorative Poster Art. Viennese Art Nouveau) 1897 – 1914. p. 5. According to the Viennese directory Lehmanns Wohnungsanzeiger Mascha’s address from 1897 to 1929 was Vienna XIII, Wambachergasse 14, according to the registration documents at the Vienna City and Regional Archive he was officially registered there from 1903 – 1929. |

| 4 | Vienna City and Regional Archive, historical registration documents. |

| 5 | Koschatzky, loc. cit. |

| 6 | Félicien Rops and his work. Catalogue of his paintings, original drawings, lithographs, etchings, soft-ground etchings, dry point etchings, heliogravure etc., and reproductions, Munich 1910; Online http://www.archive.org/details/flicienropsund00mascuoft (version dated 1.6.2013). |

| 7 | Österreichische Volkszeitung, 19.2.1929, p.6. |

| 8 | http://www.graphische.at/direktion/organisation/sammlung/plakate/plakate.php?cat=&bereich=&we_lv_start_0=0 (version dated 1.6.2013). |

| 9 | Mascha, Ottokar: Künstlerplakate und Plakatkünstler, in: Internationale Sammler-Zeitung, 1913/17, p. 250. |

| 10 | Falmbigl, Marlene: Bücher sammeln aus Leidenschaft – Privatbibliotheken in Wien um 1900 , Thesis, Vienna 2009, p. 46; online: http://www.buchforschung.at/pdf/Falmbigl.pdf (version dated 1.6.2013). |

| 11 | compare: Grohnert, René: Hans Sachs und seine Plakatsammlung, der Verein der Plakatfreunde und die Zeitschrift „Das Plakat“ im Prozess der Herausbildung, Bedeutungswandlung und Konsolidierung des Plakates in Deutschland zwischen 1890 und 1933, Diplomarbeit, Berlin/Neersen 1993. |

| 12 | I would like to sincerely thank Mr René Grohnert (Deutsches Plakat Museum) for the provision of valuable information about Mascha and “Das Plakat” (see also footnotes 9 and 10); Mascha, Ottokar: Die Internationale Plakatausstellung in Wien, in: Das Plakat 1912/2 p.76-77; Id.: Künstlerplakate und Plakatkünstler, in: Das Plakat 1914/1 p. 34 – 45: Id.: Wiener Brief, in: Das Plakat 1915/1 p. 39; Id.: Die Aufbewahrung der Plakate. Eine Rundfrage, in: Das Plakat 1915/2 s. 91; Id.: Kostbare Plakate, in: Das Plakat 1915/3 p. 126 -127: Id.: Oesterreichische Kriegsgraphik, in: Das Plakat 1917/1 p. 22-39; |

| 13 | Das Plakat:1914/1, p.60; 1914/4, p.175; 1915/3, p.127; 1915/3, p.129; 1915/5, p.201; 1916/1, p.59; 1916/3, p.152; 1916/5-6, p.267;1917/1, S.61; 1917/2, p.126; 1917/2, p.135; 1917/4, p.226; 1917/5-6, p.246; 1917/5-6, p.249; 1918/1; p.50; 1918/5-6, p.219; 1918/5-6, p.229. |

| 14 | Das Plakat: 1912/3, p.1. |

| 15 | Mascha, Ottokar: Österreichische Plakatkunst, Vienna 1915. |

| 16 | Feigl, Hans (ed.): Deutscher Bibliophilen-Kalender für das Jahr 1916, p. 103 ff. |

| 17 | Sachs, Hans: Oesterreichische Plakatsammlung von Dr. Ottokar Mascha, in: Das Plakat 1915, p. 198 – 204. |

| 18 | Sachs, Hans: Die Plakatsammlung Mascha), in: Das Plakat 1917/4, p. 226. |

| 19 | Jobst-Rieder, Marianne: Die Kriegssammlung der k.k. Hofbibliothek , in: Jobst-Rieder, Marianne – Alfred Pfabigan – Manfred Wagner: Das letzte Vivat. Plakate und Parolen aus der Kriegssammlung der k.k. Hofbibliothek Wien , Vienna, 1995, p.13. |

| 20 | Koschatzky, loc.cit., p.6. |

| 21 | Jobst-Rieder, loc.cit. |

| 22 | http://www.onb.ac.at/koop-poster/explore/#wien (version dated 1.6.2013). |

| 23 | Jobst-Rieder, loc.cit. |

| 24 | Amsler & Ruthhardt, Catalogue XCVIII, Oscar von zur Mühlen collections, St. Petersburg. Graf Gregor Stroganoff, Rome. Dr. Ottokar Mascha, Vienna, Berlin 1914. |

| 25 | Sammlung Dr. Ottokar Mascha – Wien, F.A.C Prestel, Frankfurt 1918 (=auction 69). |

| 26 | Vente Publique et aux Enchères… de Félicien Rops, Galerie Giroux, Bruxelles 1921; Online: http://www.archive.org/details/ventepubliqueeta00mascuoft (version dated 1.6.2013). |

| 27 | Handbücher der Reklamekunst. Die Sammlung angewandter Graphik, 1919. |

| 28 | Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv, Verlassenschaftsabhandlung des Bezirksgerichts Hietzing (Vienna City and Regional Archive, Hietzing District Court Probate Proceedings) 2 A 228/29. |

| 29 | For example in 2006 a poster by Toulouse-Lautrec which contained Mascha’s ownership seal was sold at “Ketterer Kunst”, http://www.kettererkunst.de/kunst/kd/details.php?obnr=100600300&anummer=300 (version dated 1.6.2013). |

| 30 | I would like to thank Mr René Grohnert for this reference. |

| 31 | Vienna City and Regional Archive, Totenbeschau (post mortem inspection) J.A. 4206/1929. |

| 32 | Obituary notice, Neue Freie Presse, 10.2.1929, p. 28. |