Julius Klinger was among the most influential artists of the German poster era before World War I and he became one of the most important innovators of Austrian poster art after 1916. Within the field of tension between the antipodes Lucian Bernhard and Ludwig Hohlwein, he found an artistic language that, while leaning toward Bernhard, had its own individual power. Formally, it was based both on graphic clarity and a sometimes radical economical use of the artistic means which today is still considered modern. Reference is often made to the typical Klinger joke: Klinger had the ability to fascinate both the man on the street as well as the gourmet in the same way. His humor was kind and ironic, without sentimentality, and accurate, without being coarse. Inspired likewise by the fashion drawing as well as the caricature, Klinger mastered both the fine, elegant line and the caricaturing overdrawing. Oftentimes, his humor was connected to his interest in fashion, his alert look at clothing, his attention for gracious movements, his love for modish draperies. Max Osborn mentioned Klinger’s origin “from the fashion business”1 and referred to Klinger’s mother, who allegedly was a well-known Vienna clothing artist. Klinger’s sense of rhythm and sound determined the elegance of his compositions, the noblesse of his colors. His mastery of the clavier of fine, broken tones and of the lapidary purity of shrill, bright colors remains unparalleled with a matter-of-factness.

1910

1910 1911

In the following period, Klinger quickly developed his own distinct poster style which he improved to virtuosity. Increasingly, the work on posters replaced the work of the illustrator. After 1905, with the printer’s growing success, Klinger joined the team of artists – Lucian Bernhard, Julius Gipkens, Paul Scheurich and Ernst Deutsch – that maintained permanent contracts with the printer. Klinger’s works quickly gained in popularity. In 1910, he was one of the best known poster artists whose professional competence was more and more in demand. On September 1, 1910, he began to teach at the newly established “Higher Technical School for Decorative Arts”. In 1911, he directed the expert class on poster art at the private Reimann-School. When the two schools were joined on January 1, 1912 and Else Oppler-Legband departed from her position as director of the “Higher Technical School for Decorative Arts”, Klinger became the director of decorative classes. Until he was drafted by the Austrian military in May 1915, Klinger remained as a teacher at both art schools. In addition, starting in 1907, he participated in discussions, gave speeches and wrote articles as a theoretician.3 He himself summarized his ideas in a critical essay in 1924 (published in 1925) titled “Das Chaos der Künste”. He particularly polemized against a transfiguration of advertising as “high” art and the dilution of advertising, serving only the consignee, through a comprehensive illustrative style that has a moral-ideological claim. In the same way, he rejected the ornament for its own sake.

His departure from Berlin was to be permanent. After the war, between 1919 and 1921, Klinger, whose good reputation had hurried on to Vienna ahead of him, created numerous posters and advertisements for the cigarette paper company Tabu.

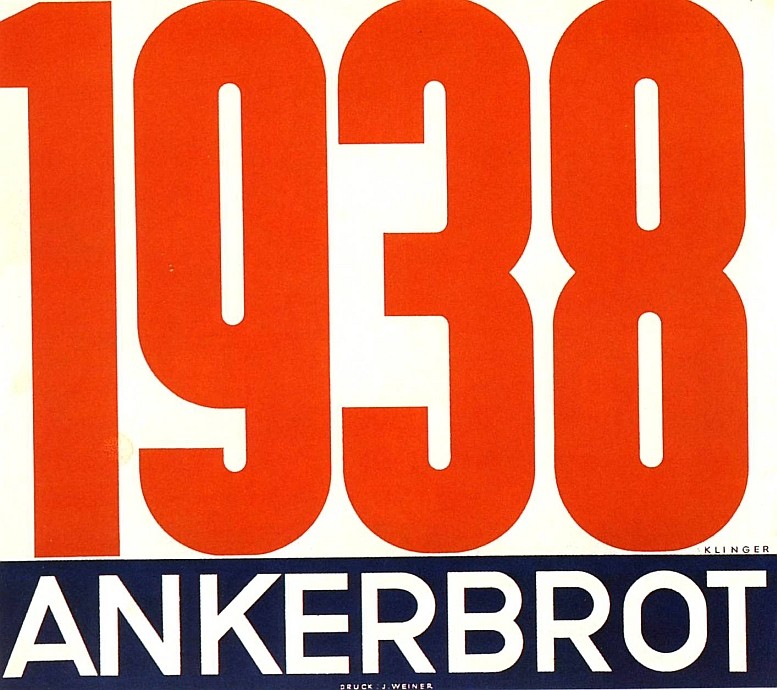

He also made posters for Mayer cosmetics and the Wasserkraft-Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft [Waterpower and Electricity Company]. Together with students and followers, he created a new artistic language which worked stronger than before with pure lines and reduced the colors mostly to red, blue, and black. With his programmatic volume “Poster Art in Vienna”, Klinger introduced himself and his colleagues to the American market. In 1928, he finally traveled to the country of his yearning. Following an invitation by General Motors, he stayed in the US from December 1928 to April 1929. Rather disappointed, he returned to Vienna.

On Wilhelm Deffke’s recommendation, whom he already knew from his years in Berlin, Klinger taught at the “Kunstgewerbe- und Handwerkerschule” in Magdeburg from March 1930 to September 1931. In connection with his studies of Deffke, Burkhard Sülzen found a biography of Klinger, written and submitted with his application for a permanent position in Magdeburg.4

Unfortunately, the Art Library in Berlin owns only seven of the poster works from the Vienna years.

The sad circumstances surrounding Klinger’s death (already mentioned in a book by Bernhard Denscher) were confirmed by the Vienna Document-Archive of the Austrian Resistance. He and his wife Emilie, whom he married in 1917, were deported to Minsk (on June 2, 1942) and killed.

1937

Revised version of: Kühnel, Anita: Julius Klinger: Poster Artist and Draftsman, in: PlakatJournal 1997/3, p.18ff. Translation: Jörn Weigelt

Notes:

| 1 | Osborn, Max: Julius Klinger. Schwarz-Weiß, in: Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration XXI, 1907 – 1908, p. 277. |

| 2 | Studio’s advertisement, ca 1900. |

| 3 | Kühnel, Anita: Julius Klinger. Plakatkünstler und Zeichner, Berlin 1997 (=Bilderheft der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, 89. Heft). Klinger’s theoretical views are recorded in the exhibition catalogue, p. 28ff. |

| 4 | Ibid, p. 23ff. This biography is published for the first time in this catalogue. |